Weighing the Impact of the Trump Tax Cuts

As 2017 wound down, the Trump Administration was seeking out a large legislative win to point to. They certainly got one with the last-minute passage of its tax cut bill for both corporations and individuals. As the measure was signed into law by President Trump shortly before Christmas, the debate began as to just what it would mean for the economy and the financial markets.

The economic analysis provided by both its proponents and detractors has highlighted how deep the chasm is over whether this tax cut measure will ignite economic growth and generate enough new tax revenue to pay for itself or simply blow a hole in the US federal budget. As William Dudley, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, stated earlier this month, “While the recently passed Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 likely will provide additional support to growth over the near term, it will come at a cost….The legislation will increase the nation’s longer-term fiscal burden, which is already facing other pressures, such as higher debt service costs and entitlement spending as the baby-boom generation retires … the current fiscal path is unsustainable. In the long run, ignoring the budget math risks driving up longer-term interest rates, crowding out private sector investment and diminishing the country’s creditworthiness.”

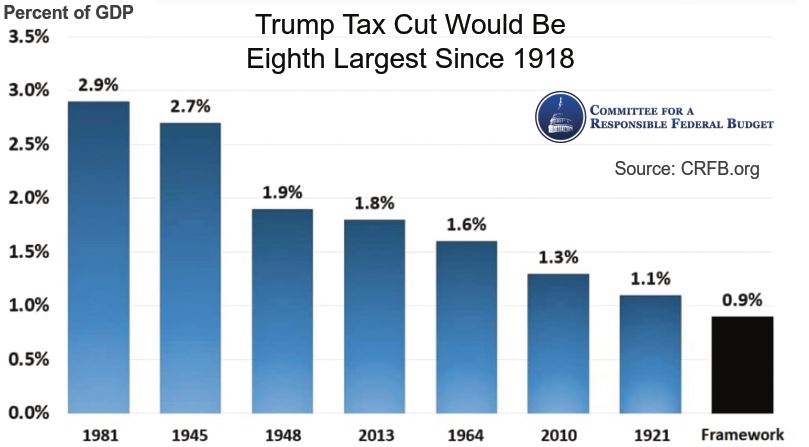

Dudley and others have expressed caution on the tax cuts because they think there is enough upward pressure on interest rates with current economic momentum. The tax cuts will only add further stimulus to the economy (all else being equal) and this would put further upward pressure on already rising interest rates. Ask almost any economist and they will usually answer that low interest rates are often more powerful than lower taxes as an economic tool. In addition, as seen in Figure 1 below, though there is great hope and excitement around the Trump tax cut and what it will accomplish, it is only the eight largest US tax cut since 1918.

Figure 1: Trump Tax Cut Would Be Eight Largest Since 1918

Source: CRFB.org

The tax cuts received very little debate from either the perspective of their impact on the budget deficit and national debt. Since tax cuts reduce tax revenue to the federal government, then there must be an offset that comes from either the ability of the tax cuts to stimulate faster economic growth or a reduction in spending has to be made. Otherwise, the deficit and debt will rise. If the tax cuts result in a meaningful stimulus to the economy, then the economy will generate new tax revenue that would keep the budget deficit contained. Currently, the US has a national debt of about $20 trillion—almost by necessity a lid must be maintained on interest rates or an explosion in interest costs on the national debt will rip through the economy.

The Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation estimates that the tax package will grow GDP by 0.7% annually for the next decade which will raise net tax revenues by about $385 billion but still add an additional $1.1 trillion to the national debt over the next ten years.

While this will play out in time and estimates are bound to vary from whatever the end result is, we are at best mixed on the tax package as there seems to be little or no concern amongst policymakers for what to do about the budget deficit and the coming challenges that an ageing society will bring in terms of demands on healthcare and Social Security. To be fair, this is not a US specific problem – outside of Africa, the Middle East and parts of Asia – many nations are also facing challenges related to ageing societies.

Debate Surrounds the Economic Impact

By mid-January, corporations will begin announcing their profit numbers for the fourth quarter of last year. At this point, investors are confident that the best economic growth rates since the last recession will enhance the bottom line of corporate earnings. Most economists’ estimates for GDP growth center around 2.7% this year for the US economy. Interestingly, JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon has shredded his own economists’ forecasts and was quoted in a Fox Business News interview saying that “Four percent economic growth this year is possible.”

Countering Dimon is the opinion of Glenn Hubbard, the former chair of the Council of Economic Advisors in the George W. Bush Administration. Hubbard believes tax cuts will be not as helpful as its proponents suggest but not as bad as its critics claim. Hubbard (perhaps somewhat strangely) told the Wall Street Journal that “It’s not going to raise us off to 4% GDP growth. But it’s not going to kill 10,000 people a year.”

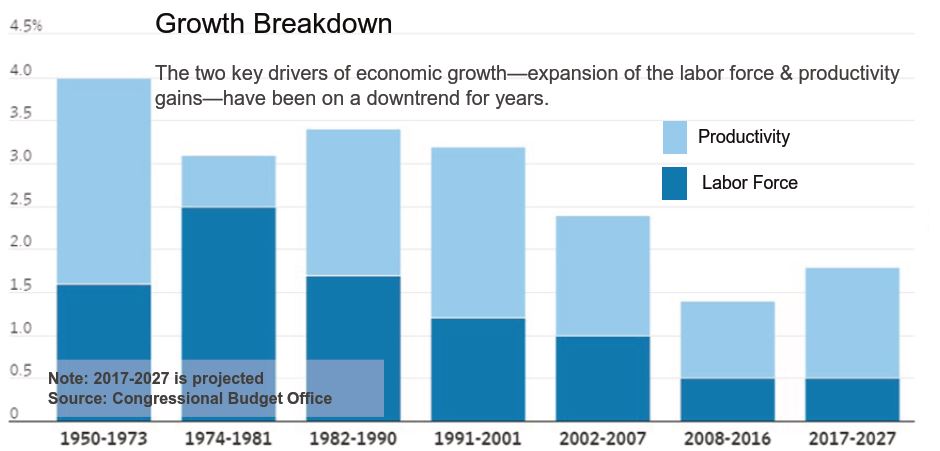

Those who are taking a cautious approach to the impact of the Trump tax cut point to the fact that the economy’s long run growth rate is determined by how many people are working (labor supply) and how productive they are (productivity). As the chart shows below in Figure 2, from 1950 to 2016, inflation adjusted annual potential growth of the US economy averaged 3.2% according to the Congressional Budget Office. Going forward, many economists believe that due to an ageing society and stagnant productivity growth rates, the math does not seem to work for higher economic growth. However, economists have been known to be wrong before and sometimes widely missing the mark. Thus, low economic growth for the foreseeable future is not a foregone conclusion but the challenges are certainly there.

Figure 2: Growth Breakdown

Source: Congressional Budget Office. January, 2018.

Earlier this month, at the 2018 annual meeting of the American Economic Association, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco economist John Fernald told a panel that the slower than average economic recovery since the last recession was simply reflecting changes in workforce demographics and productivity that have been underway for some time and are likely to persist. He believes that “The headwinds to a substantial pickup in growth are fierce.”

There seems to be very little in this tax cut that is aimed at addressing these challenges. The only item in the tax cut passage that might help to raise GDP growth over the long term is that it allows immediate expensing of some capital investment by corporations. This investment can make labor more productive which is a key ingredient of economic growth. But it is up to corporations to take advantage of this and that will depend on their priorities and the opportunities they see from making such investments.

What About Corporate Profits?

Corporations will see their statutory tax rate drop from 35% (though very few pay anywhere close to this rate due to deductions and other rules in the tax code) to 21%. Standard & Poors estimates that prior to the tax cut, the effective (actual) tax rate for the S&P 500 companies was 26-28%. But since most businesses do not pay the 35% rate to begin with, the actual reduction will be about 5-7% in the effective tax rate for most companies. In other words, most companies pay a tax rate of about 25-26% and that will drop to 21%. Clearly, this is a positive for corporate after-tax profits.

Estimates for earnings for the S&P 500 companies in the US are estimated to rise from $134 to $144 due to the tax cuts.

With the incentives for corporate investment laid out in the tax package, the US will draw investment from abroad. The European Union is already fearing an exodus of investment capital and has already been complaining that the US tax cuts run counter to international agreements and would undermine international trade. Canada will likely experience a talent and capital drain to the US – as was the case in the 1990s and early 2000s due to the differentials in corporate and personal taxes as well as regulatory barrier differences. Business groups in Canada have stated they fear the tax differentials more than the demise of NAFTA.

Repatriation of Cash Excites Investors

Wall Street and many investors are particularly excited about the repatriation benefits introduced into law. This part of the tax law allows US companies to repatriate (bring back) profits held in overseas subsidiaries for tax reasons. US corporations have over $2.8 trillion in profits and investments stashed abroad that they were reluctant to access because of the tax expense that they would incur under the prior higher US tax rates. Under the most optimistic scenario, once this cash comes back to the US, it would be invested in new plant, property and equipment (i.e. corporate investment). This in turn would lead to more jobs, higher productivity and hence the higher economic growth that Figure 2 above shows has been on the wane for decades.

Based on what corporate America has said so far, this is more idealistic than practical. A recent survey from Bank of America Merrill Lynch asked 300 large US corporations what they would do with a foreign profits repatriation tax break and 65% said that they would use their savings to pay down the $6 trillion corporate debt U.S. companies have built up; 46% said they would use the proceeds for stock repurchases; 42% said that mergers and acquisitions would be a priority and capital expenditures were down at 35%. (The numbers don’t add up to 100% because companies could check more than one use of the cash.)

We would question the use of this cash for stock buybacks at current valuations for most corporations. Simply put, spending money to buyback stock at elevated valuations makes no sense from a long term perspective. It is akin to throwing the money away. Critics will point to the fact that executives are motivated to get their stock prices up since so much of their compensation depends on the gains in their stock price and buybacks are a way to do that.

Like anyone else, we would welcome a short-term boost to the stock market from a repatriation fueled stock buyback boom. But we would be fooling ourselves if we think this was a wise use of cash or that it would provide a long-term boost to the economy. When repatriation was tried once before in 2004, companies brought back $300 billion to the US but 80% of it was used to buy back stock according to data from Bank of America. The short-term boost to the stock market was then followed by job cuts by many of the largest cash repatriating companies. Even the American Enterprise Institute – a proponent of lower taxes – has stated repatriation will do little to boost the economy.

Apple Inc. is getting the most attention because it has over $260 billion overseas and has stated it expects to pay $38 billion in repatriation tax—indicating that it would bring most of its cash and investments back to the US. While this tax inflow will certainly help the budget, it is a one time item.

Impact on Corporate Earnings

Currently there is nothing on the horizon that is signalling an economic slowdown or recession at home or abroad. The data shows that a record low number of nations are currently in recession. The global economy is accelerating at a pace that has not been seen in over a decade. Barring an unexpected event that shocks the global economy, 2018 will be the strongest year for globally synchronized economic growth since the 1950s. Even if critics of the Trump tax cuts prove to be correct, the underlying economic momentum will continue to power the economy forward. This will in turn help to increase corporate profits.

Our main concern about the tax cut seems to be an issue that never seems to get the attention it deserves and that is the US budget deficit. Even before the tax cut, the path towards higher interest rates was clear. The tax cut only raises the interest rate forecast which means the US debt becomes more expensive to carry. Further, interest rate increases can often act as a brake on the economy – far surpassing the stimulus from the tax cut. For these reasons, we think it is important to balance the short-term positives of tax reform against the potential of long-term negatives.