War on Inflation Awakens the Bear

In This Issue:

- Policy errors & unforeseen events

- Same as ever—energy Is a key to inflation

- Recession—debating its severity

- Inflation likely closer to peaking

- Central banks will do what it takes

In Spring 2020, the global economy entered the deepest recession since the Great Depression. Fortunately, it also turned out to be the shortest recession on record – lasting barely two months. Powered by a limitless level of stimulus from governments and central banks, the global economy roared back out of the downturn. The global economy’s rate of growth surprised even the most ardent optimist as growth rates reached levels not seen for over three decades. But one of the things economists fear the most is “too much of good thing” because an overheated economy that has persistent demand and not enough supply of goods and services is one that has to be slowed down. Historically, that has meant a policy of higher interest rates.

Blaming the Policymakers

Much debate exists today about whether or not policymakers are to blame for the inflation problem engulfing the world today. As is usually the case, there is no simple and straight answer to this question. When it comes to fiscal policy (tax cuts, government payment to households and spending on new programs) it can be argued that governments did not rein in their largesse. Motivated in part by the popularity of such programs and a wish to “Build Back Better”, many governments saw the rebound from the pandemic as an opportunity to hit a reset button and change course on energy, taxation and social policies.

But when we look at monetary policy, were ultra-low interest rates and increases in the money supply that ended up in the financial system too much of a good thing? On the surface – it surely seems that way. But when we look at it at a deeper level – what was a central banker to do? If stimulus was taken away too soon, many economists felt that the economy could go back into recession – especially since global supply chains were not back up to full capacity and the threat from successive waves of COVID infections loomed large over the economic outlook. In short, surely there were errors made with the benefit of hindsight but given the unprecedented circumstances, most policymakers deserve praise over scorn.

Energy Prices: The Root of the Problem

While these and other policy errors by governments and central bankers have undoubtedly contributed to the rise in inflation, it is the relentless rise in energy prices that has had the biggest and most sustained effect on inflation. Thus, of the policy errors energy policy is having the biggest impact on inflation today.

Oil supplies are tight relative to demand and the energy industry is showing, at best, a partial unwillingness to spend more to increase supply through increased investment. The energy industry wants assurance from governments in North America and Europe that before it spends the needed hundreds of billions of dollars to find new energy supplies, that they will not have spent that enormous sum in vain by being served with “green” operating restrictions in the future. The shareholders of these companies will simply not accept this risk. Meanwhile the heavily touted green energy industries of the future have demonstrated they are nowhere near ready to support modern economies and global coal consumption has rebounded to fill the void.

Nearly a Decade of Underinvestment

Late last year, the International Energy Forum, an organization of energy ministers from over seventy nations, estimated that the global energy industry will have to increase investment to find new energy supplies from $200 billion currently to about $550 billion over the next several years. But energy companies are pointing to pressures from governments, environmental groups, activist investors and even their own shareholders who are demanding cash profits be paid to them instead of pumped back into exploration budgets to find future energy supplies.

In the pandemic’s immediate aftermath, the commitment to “Build Back Better – in which governments would begin the task of moving the world away from fossil fuels – has unfortunately backfired spectacularly. The world was not ready for this policy shift and in many ways – the green transition has been set backwards. Some European politicians who were previously enthusiastic supporters of a green energy transition have become lukewarm in their support as they scramble to find ways to overcome inflation fueling energy prices. In short, they have stated publicly that the transition will have to wait.

The crisis and catch-22 of the energy transition is best summarized by Daniel Yergin – one of the foremost energy experts in the world. Yergin stated that “Additional layers of complexity and the uncertainty that it brings is fostering an environment of pre-emptive underinvestment for oil and gas supply, where capital expenditure lags demand.” In short, Yergin is saying if the world wants lower energy prices, give the global energy industry some degree of comfort. Many energy experts have begun to express an opinion that governments need to recognize that an energy transition to a low carbon world will take time. They also fear that if energy prices do not come down, the world will revert to more destructive sources of energy such as coal and wood.

An Unwelcome Surprise

Setting policy at the best of times is fraught with the risk of the unknown and unforeseen. While the consequences of energy underinvestment were easy to see, an unexpected curveball came in the form of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Within eight days of the invasion, oil prices rocketed from $95 per barrel to $132 per barrel – a 40 percent rise in a little over a week! With this conflict, the world was in for an additional oil shock as Russian energy exports to Europe have been reduced through sanctions imposed on Russia. Russia has countered by holding back the supply of natural gas to Europe as it tries to break Europe’s will to stand up to its invasion of Ukraine.

… And A Pleasant One

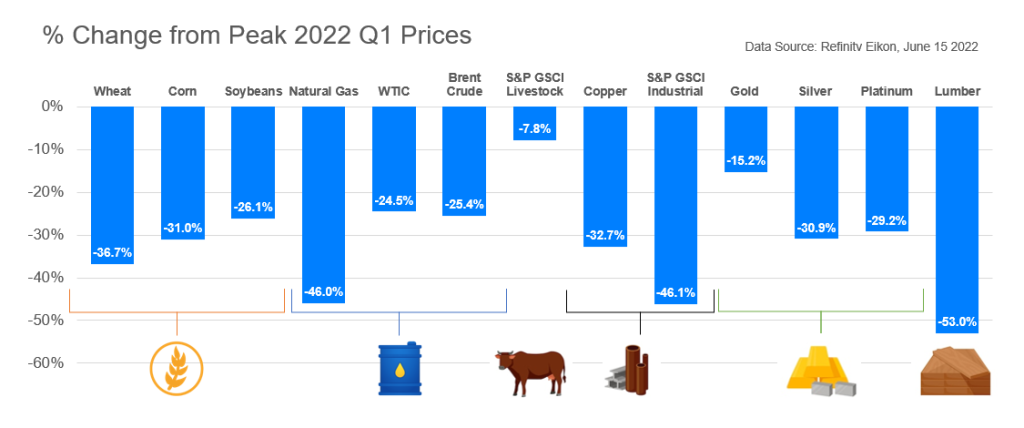

Since the onset of the pandemic, it has seemed like the world has lurched from one crisis to another. Pleasant surprises have been in short supply. However, an unexpected source of good news has been the easing of agricultural and energy commodity prices in the financial markets. As the chart above shows, commodity prices have come down sharply even with the risk of supply curtailments due to the war in Ukraine and other challenges. That is a signal that traders who set the prices of food, energy and base metals are comfortable – at least for now – in terms of supply being able to keep up with demand. These lower commodity prices should begin to reflect themselves in the inflation numbers heading into the Fall.

Moderating commodity prices are important in the fight against inflation since commodities are the inputs to everything produced in the world. Perhaps the most important commodity of all is oil. It is not only used for most of the world’s transportation needs but oil (along with natural gas) is an input for over 6000 everyday products ranging from hand sanitizer to solar panels to smart phones. As the price of energy rises, the cost of making these products goes up. Thus, the manufacturer has two choices – either absorb the higher cost of oil and make less profit or pass it along to the consumer. This rather simple example of oil’s role in inflation helps to show why the price of oil matters.

According to the research consultancy Energy Aspects, oil prices are being pushed down by financial conditions in which speculators and other investors are selling their crude oil holdings to raise cash. This factor – rather than a drop in demand or a build up in oil supply – is the reason oil prices have come down and should result in an easing of gasoline prices. This will have a meaningful impact on lowering inflation.

The drop in oil prices should not bring about complacency. The main reason that oil prices have come down is that for now – oil markets are comfortable that risk of supply disruptions from Russia are priced in and future risk levels have abated. Furthermore, the demand for investments tied directly to oil by financial actors such as trading houses and hedge funds and other investors is estimated to be about 28-30 times that of actual demand for physical crude oil. As interest rates rose and investors rushed for cash due to volatile financial markets this year – these financial actors had to sell their oil investments – thereby sending the price of oil down. Despite everything, the incredibly tight oil markets are going to persist for some time. Current data shows world oil production is barely matching demand – with shortfalls being met by the drawdown of oil inventories. The US Energy Information Administration estimates that prior to Q2 2022, global oil inventories have been down for every quarter for the last two years.

Recession: Probability vs. Inevitability

The financial markets are attempting to price in the probability of a recession and what its impact would be on the value of global equities. The fear is that if inflation does not come down quickly enough then the probability of a recession rises. This is because the US Federal Reserve and other major central banks have unequivocally stated that if it takes an economic slowdown or a recession to bring down inflation – then that is an acceptable tradeoff. Clearly, the economy’s ability to avoid a deeper recession depends on how fast inflation can come down. If it moderates on the back of falling commodity prices, easing supply chain related shortages and a still strong but slowing labor market – the US economy (the largest and most important) will likely achieve the elusive soft-landing and avoid a recession.

The US consumer is the most important economic actor as consumer spending accounts for almost 69 percent of the US economy and about 16 percent of the global economy. At this point, a strong but slightly moderating jobs market and still flush savings levels are insulating US consumers from the effects of inflation. However, it should be noted that at lower levels of the income spectrum, households across the world are suffering.

Financial markets are trying to price in the probability of a recession and what its impact would be on the value of global equities. The fear is that if inflation does not come down quickly enough then interest rates will have to continue to stay elevated or continue to be raised.

Given the surprises and curveballs of the last two years – it should come as no surprise that amongst those voices calling for a recession, there is a significant group that says the recession will be uniquely mild. In other words, it will not be one that causes significant job losses. The optimists point to the fact that as the recession looms there 11.2 million job openings in the US but only about 6 million unemployed individuals. Said another way, if those 6 million unemployed individuals could be slotted into one of those 11.2 million job opening – there would still be 5 million jobs waiting.

While the US appears to be better positioned than most of the developed world to cope with a recession – the same cannot be said for Europe or Canada. In Europe, the economy has been sluggish for nearly two decades and in Canada – it remains to be seen how its economy adjusts to a wildly overindebted household sector.

A key question then is “Would a mild recession be enough to slow down inflation?”All else being equal, history shows that an economic slowdown should coincide with a moderation in inflation pressures.

Inflation Beginning to Peak

Central bankers have likely begun to notice some of the softening of inflationary pressures but it is too soon for them to publicly declare victory in the inflation fight. This would only serve to fire up the economy and central bankers would be repeating the mistakes of the 1960s and 1970s when inflation was fought with a half-hearted commitment. The result was inflation became entrenched in the expectations of businesses and households and it took the raising of interest rates to double digits and a long and deep recession to put the inflation genie back in the bottle. Recognizing the significant cost that had to be endured then, it is no wonder that central bankers have had to be uncharacteristically explicit that they will do what it takes to tame inflation. Thus far, the financial markets are taking them at their word!