The US National Debt Challenge

In This Issue:

- 2001 consensus was for the US to be debt free by 2010

- Rising spending and the pandemic spiked debt

- Facing hard choices at a challenging time

- Canada showed debt can be solved

For over a generation, fears about the US national debt have ebbed and flowed. A lucky combination of events helped to keep pushing the potential for a debt crisis off into the future—allowing the US to kick the can down the road. This allowed politicians to avoid having to present to voters some tough choices about the affordability of the various programs and services provided by the US government. It was politically easier to borrow on the national credit card rather than raise tax revenues or cut spending. For clarification, the national credit card refers to the US Treasury – like all governments – being able to go to the bond market borrow what it needs from investors.

False Hopes

One of the few times that the national debt was a major issue for voters was in the 1992 presidential election when the deficit exploded to 4.5 percent of GDP. Eventually, a booming economy that generated strong growth in tax revenues and fortuitous circumstances that allowed defense spending to be reduced helped to arrest the budding debt problem. By 2001, the Clinton Administration left a $240 billion budget surplus for the Bush Jr. Administration. The worries about the national debt were replaced by fantastical thinking that the US was set for continuous budget surpluses that would eliminate the national debt by 2010. At the same time, investors became worried that the bond market would not function smoothly because the supply of US Treasury bonds in circulation was to largely disappear by 2010 based on the idea that if there is no debt, there would not be any Treasury bonds in circulation. This was seen as a problem because the interest rates on Treasury bonds act as benchmarks for other parts of the bond market.

As Congress contemplated what it should do in the face of the expected budget surpluses and the elimination of the national debt, it called on then Chairman of the Federal Reserve Allan Greenspan for his thoughts on future tax policy. At the time, Greenspan was celebrated as “The Maestro” based on his stewardship of the US economy. Greenspan told Congress that he would endorse the policy of the Bush Administration to cut taxes because tax revenue would be far in excess of what the US government needed to meet its expenditures. If tax cuts were not enacted, Greenspan argued, it would leave the federal government in a position where it would be accumulating cash with nowhere to spend it.

Deficits Roared Back

It did not take long for the mirage of endless budget surpluses to be replaced with the returning fears of a debt problem. The budget deficits returned as the US economy underwent a recession by 2001 that coincided with the end of the technology sector boom. US tax revenues began to decline and spending commitments went up. The result was the return of budget deficits that ended up being piled onto the national debt. The dream of paying down the debt was a one-year fantasy.

The recession also coincided with the events of 9/11 and military spending began to rise quickly. The wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and combat operations in Syria and Africa are estimated to have cost over $4 trillion over twenty years. Some estimates are considerably higher as the definition of what costs can be attributed to these events varies widely. US expenditures for the war in Afghanistan alone amounted to spending of about $275 -$300 million per day over a 20-year span.

Pandemic Spending Spikes Debt

With US combat presence in Iraq long over and operations in the Afghanistan conflict entering their final years, the hope for a return to more sustainable spending were shattered with the onset of the pandemic. The impact on the economy exploded the national debt yet again. Beginning in early 2020, the US government – like so many others – responded to the deep downturn in the economy with unprecedented levels of spending and other fiscal incentives to help the US economy steady itself. In a little over 2 years, the US government provided nearly $5 trillion in additional spending and other fiscal measures. This further ballooned the national debt. It should be noted that nearly all politicians and economists forged a rare moment of agreement in their support of these stimulus programs. Given the magnitude of the downturn that the global economy faced, stimulus at the time was an easy policy to support and one that would be hard to argue against given the challenges that arose. Unfortunately, the spending has continued even as the economy made a faster than expected recovery and was long past needing government support programs to continue its recovery.

Path to Fiscal Crisis

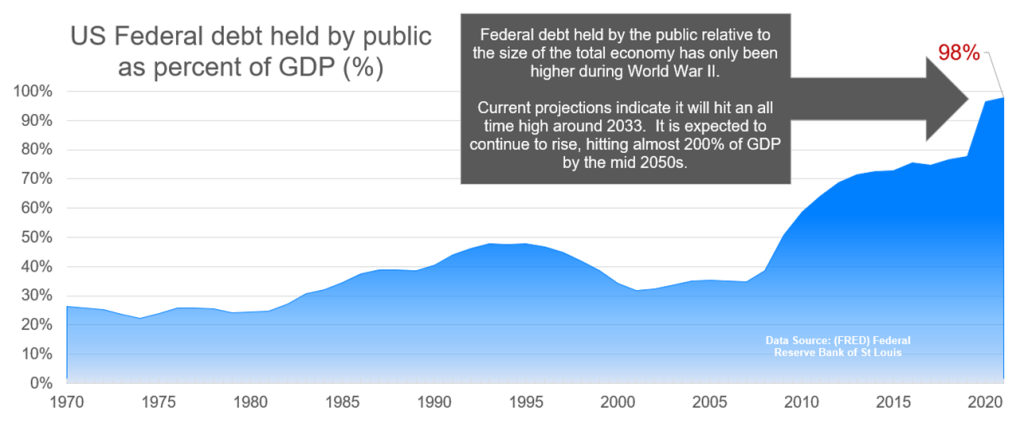

Given the various shocks to the economy since the turn of the century – along with overseas military commitments and commitments to mandatory spending programs for healthcare and social security – the US national debt sits at $33.5 trillion. For comparison, the national debt stood at $5.7 trillion in 2001 with the goal of being debt free by 2010.

Since the 2008 recession and the Great Financial Crisis, the US has been able to largely avoid having to deal with the national debt challenge because low interest rates made it easier to carry the debt. In addition, the US Federal Reserve had bought up about $7 trillion of the debt issued by the US Treasury by making purchases in the bond market. These purchases also helped to keep interest rates low on the US debt since the Treasury had a ready and willing buyer on hand.

It is important to note that the Federal Reserve is required by law to return to the US Treasury any interest it earns from Treasury bonds. This is what the laws governing the Federal Reserve require. In 2021 the Federal Reserve paid back $109 billion of interest income earned from the Treasury and returned another $76 billion in interest in 2022. The US can no longer count on this as the Federal Reserve is no longer trying to keep interest rates low as it battled inflationary pressures.

Rising Rates and Reality

A combination of luck, low interest rates and a steady demand for US debt (bonds) made those who worried about the steady rise in the US national debt seem like they were crying “The sky is falling” and were quite often swept aside in the national discourse.

Unfortunately, the times are changing. The luxury that US policymakers once had of not having to deal with the debt problem has been all but taken away by rising interest rates, rising spending and a reduced demand by both foreign and domestic investors for US debt. The US finds itself in the unfamiliar place of having to think about where the buyers of its debt will come from so that it can finance its spending obligations. The challenges are breathtaking. When interest rates were at historic lows in 2020 and 2021, the US had the chance to lock in those very low interest rates on its debt by issuing long-term bonds. Instead, it chose to focus on locking in short-term interest rates that were less than 1 percent rather than locking in borrowing rates of 2% for 30 years. Today, borrowing for 30 years would cost the US Treasury more than 5 percent annually.

The return of inflation has forced the US Federal Reserve to halt its purchases of US Treasury bonds as it raises interest rates to cool inflationary pressures. At the same time, it has been aggressively raising interest rates to unwind the stimulus it had put into place during the pandemic. Against this backdrop, the US now faces a breathtaking hurdle where almost one-third of all outstanding US debt will mature over the next year and a little over half will mature over the next 3 years. The interest rate on this maturing debt will be significantly higher.

Deficit Rises While Economy Grows

History shows that budget deficits fall as economies grow. But since the pandemic, the US budget deficit has been slow to fall. The current fiscal year shows the US budget deficit will be about $2 trillion—fueled by a drop in some sources of tax revenue and rising spending. One area that has the attention of deficit watchers is the rising tide of interest costs on the debt due to the escalation of debt while interest rates have risen. Current year projections show interest costs in the current year will cost the US government about $600 billion – up 50% from 2019 levels. This figure is significant for another reason – it is on track to exceed defense spending within a decade.

Current global conflicts already require a significant resource commitment from the US with more likely as current defense experts – and some US allies – believe that the US must raise its ability to meet these threats. This is where the national debt challenge is going to become quite apparent. Interest costs on the national debt are going to approach $900 billion per year within a decade. Given the geopolitical challenges facing the US and its allies in Europe, Asia and the Middle East – there is going to be a challenge for policymakers to meet all of the commitments of today and any future escalations that might arise. This now brings added prescience to the 2010 warning from then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Mike Mullen, when he told Congress “The most significant threat to our national security is our debt.” The US is being pushed into a corner where it must make hard fiscal choices about how much it can continue to do to meet threats from abroad while meeting the needs of its citizens.

Bond Buyers Needed

Given the supply of new bonds issued by the US Treasury to fund even greater spending, the US is facing a problem rarely seen before. It needs buyers for its debt so it can fund its budget. At home, the US Federal Reserve is no longer a buyer as it wants to keep taking stimulus out of the economy.

Internationally, nations such as China, Japan and the oil producing nations of the Middle East are no longer eager buyers of US bonds. So much debt has been issued by the US in the last several years that international buyers have a reduced appetite to keep buying. China and Japan are the two largest holders of US Treasury bonds. China’s reluctance to continue buying US debt issues at the same pace as in past years is due to a combination of factors. One reason is that China’s economy is weak and its currency has been falling. If it were to sell its own currency to buy US dollar denominated Treasury bonds, its currency would fall further in value. In addition, China’s relations with the US have been quite cool in the last several years and China likely wants to risk having so much of its currency reserves invested in the US. Over the last decade, its efforts at trying to diversify away from the US has led China to increase its gold holdings from 1000 tons to 2200 tons.

Seeking a Path Forward

The rapid spiral of the US national debt is going to force the US to make some hard choices of what spending it can cut and how much it can raise taxes. This is easier said than done as passing a budget in the current political environment seems like a distant prospect. For this reason, two of the three major credit rating agencies have downgraded their ratings on US debt.

There is some hope for the US. Nearly 30 years ago, a heavily indebted Canada went to the bond market to issue bonds for yet more borrowing and the bond issue received no bids from buyers. The market was shutting off the credit tap. Alarmed, the Canadian government took the scissors to the budget and implemented large spending cuts. Canada went from debt pariah to running consecutive budget surpluses and by 2008, Canada’s debt to GDP fell to 29 percent from nearly 100 percent in only 15 years. Since then however, Canada like the US has been accumulating debt again at a rapid pace.

In 2003, Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill told Vice-President Dick Cheney he was worried about the pending tax cuts and the potential for a large increase in the budget deficit. Cheney replied “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter.” Perhaps they did not matter then but today, the markets and foreign buyers of US debt are saying “Deficits do matter.”