The Return of the Old World Order

In This Issue:

- War in Europe & the old world order

- Conflict brings energy security to center stage

- Economic growth forecasts lowered

- Evolving perspectives on ESG Investing

As the COVID pandemic peaked and the world started to transition back to some semblance of its pre-pandemic characteristics, it is clear that normal as it was is not going to be on the horizon anytime soon. Normal would be defined as a world with well functioning supply chain issues, contained inflation pressures and anchored interest rates—along with a mostly fragile stability amongst the major nations of the world. With hindsight, it seems the notion that the world would pick up where it was pre-COVID is misplaced. Looking back at most any period of history, we can see that the unexpected has an ability to upend consensus more frequently than one might think.

Historical Upending

On September 11, 1990, a hopeful US President George H.W. Bush told the US Congress of his wish and hope to see a “a new world order … an era in which the nations of the world…can prosper and live in harmony.” On November 1, 2021, US President Joe Biden told a global gathering of world leaders in Scotland at the UN sponsored COP 26 climate change conference, “There’s no more time to hang back or sit on the fence or ague amongst ourselves …This is the challenge of our collective lifetimes, the existential threat to human existence as we know it and every day we delay, the cost of inaction increases. So, let this be the moment when we answer history’s call here in Glasgow. Let this be the start of a decade of transformative action.”

These two quotes were selected for several reasons; for the purposes of this newsletter they show how grand ambitions can be upended by the unexpected. In the case of the vision laid out by President Bush, it was the struggle against global terrorism and wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere. For President Biden and so many other leaders who wanted to “build back better” after the pandemic – their vision has been pushed to the sidelines by the war in Ukraine and the fight against inflation.

Oil Refuses to Exit the Stage

Both before and after the pandemic, the oil industry was being assigned to the scrap heap by many voices – having gained the status of environmental pariah and a relic of a soon-to-be bygone era. Policymakers and investors began to coalesce around the idea that the world would begin a sustained a trajectory to a fossil free world.

The war in Ukraine and the oil supply constraints we have noted in previous quarterly commentaries have conspired to upend the emerging consensus and have once again planted oil in its traditional role of being at the center- or at least a central actor – in global conflict. The words “traditional role” are appropriate when it comes to oil. Based on the 2013 findings of a policy brief published by the Belfer Center at the Harvard Kennedy School which found that since 1973 between one-quarter and one-half of wars between nations have been linked to oil.

As the Russian army rolled into Ukraine, much of the world formed a common policy to place economic sanctions on Russia – the world’s third largest oil producer after the US and Saudi Arabia. However, Russian oil exports of about 8 million barrels per day make it the largest exporter of oil in the world. Nearly 5 million barrels per day (60 percent of Russian oil exports) were flowing into Europe and about 1.5 million barrels (20 percent of Russian oil exports) were going to China.

Given Europe’s dependence on Russian oil and gas, the Russian side certainly would have assumed that European resolve to counter Russia’s invasion would not be a significant impediment given Europe’s existing energy supply challenges. In addition, last year the US gave Germany its approval to allow for German access to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline to bring even more Russian natural gas that bypassed land routes through Ukraine. However, in a surprise move to many – including Russia – Germany sanctioned the pipeline project and made it dormant in retaliation against Russia.

North America: The Arsenal of Energy

A key part of the Russian calculus in its invasion plans was that given the crisis in European energy markets which has caused a skyrocketing of energy prices on the continent – Europe would be reluctant to impose economic costs on Russia (i.e., reduce or halt imports of energy from Russia). This seems to be a miscalculation as Germany has said it will end Russian coal imports by the summer and plans to wean itself off Russian oil by year end. It should be noted that Europe is continuing to buy energy from Russia while it secures other supplies.

From an economic perspective, the importance of North American oil and gas to the world economy cannot be overstated. In the Middle East, the only two nations that can meaningfully increase their oil supply to help bring down prices are Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. So far, both nations have refused US requests to increase oil production. Their decisions are driven only partly by economics.

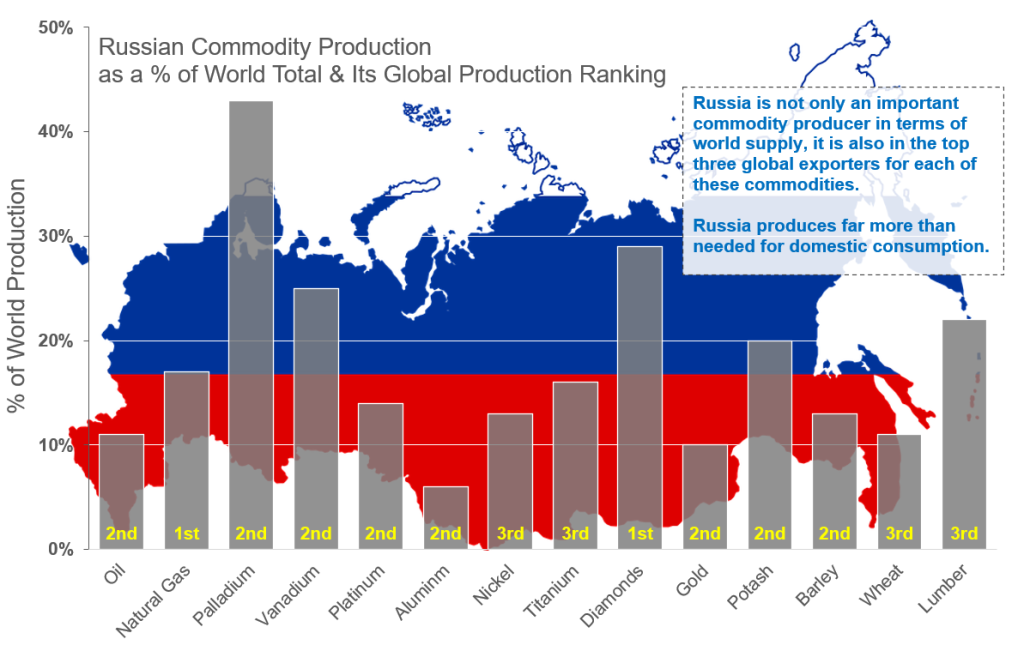

As the chart above shows, it is not only oil land gas that Russia provides in significant quantities to the rest of the world. It is a significant supplier to the world of virtually every major commodity. The challenge of the world is to figure out how to reduce the threat from a reduction of supply from Russia.

War & Oil Creating New Friendships

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE want the US to take a tougher approach to Iran’s nuclear weapons program and to stop criticism of the two nations’ intervention in the civil war in Yemen. Once again, war and oil make for a complex and convoluted situation. Perhaps an even better illustration of how the “Build Back Better” agenda has been put on its backfoot is the fact that the US has even approached the already economic sanctioned nation of Venezuela to help get Venezuelan oil back on the markets. However, years of corruption and underinvestment have decimated Venezuela’s oil industry – despite it owning the world’s largest oil reserves.

Natural Gas: The Other Energy

In addition to oil, Europe needs an alternative supply of natural gas. In 2021, about 40 percent of Europe’s natural gas needs were met by Russia. For its part, Canada – which produces about 5 percent of global natural gas supply – is in a very poor position to help Europe with its supply. This is because Canada does not have a single liquified natural gas (LNG) export facility which would allow Canadian natural gas to be liquified and loaded onto tankers bound for Europe. Since 2011, there have been 18 LNG export facilities proposed in Canada with only one under construction (on the West Coast of Canada). In comparison, the US has built seven LNG plants since 2011 with 5 more under construction and another fifteen approved for construction. Clearly, Canada has some work to do if it is to help Europe.

It is speculated that at a recent bilateral meeting between the leaders of Canada and the UK, the UK was pressing Canada to do more on the energy front – and thus far, it seems Canada has remained lacking from the European perspective. Given that Canada produces 5 percent of the world’s natural gas and the US does not need it – Canada should join Australia and Qatar in stepping up to help Europe in its hour of need.

Europe has asked Canada to do more. Canada’s Natural Resources Minister, Jonathan Wilkinson, stated that Canada can only raise oil production by about 200,000 barrels per day – an increase of less than 2 percent from current levels! After meeting with his European counterparts last month, Wilkinson also surprisingly offered that Canada is looking at reducing consumption in Canada to free up supplies for export to Europe!

Publicly, Canada has stated that while it will be able to offer a marginal increase in oil production, it would not alter its pledge to slash greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) by at least 40 percent over the next eight years.

Shifting Priorities

One of the greatest surprises of the war in Ukraine is that Germany has undergone a 180-degree reversal in direction on not only its energy policy (i.e. goal of eliminating Russian imports) but also that it will begin an immediate increase of over 100 percent to its military spending – taking it from €47 billion in 2021 to € 100 billion in 2022. Only days after the start of the war, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz told the German parliament “We will have to invest more in the security of our country to protect our freedom and democracy.”

Following Germany, Italian Prime Minister, Mario Draghi, told the Italian Senate in March that Italy would not look the other way and that the “…threat from Russia is an incentive to invest more in defense than we have ever done before.” Draghi also went on to say that the Ukrainian conflict “marks a decisive turning point in European history and shatters the illusion of taking for granted the achievements of peace, security and well-being obtained by the generations that preceded us with enormous sacrifices.”

Draghi’s statement contrasts incredibly with the vision of the new world order laid out by President Bush in 1990 and by inference – Draghi would say that the “challenge of our lifetimes” has changed from the one laid out by President Biden in November of last year.

The statements from the leaders of Germany, Italy and many other nations underscore their commitment to raise spending on their increased military needs. Financial markets have begun to anticipate the increased future profits for the aerospace and defense companies. Their shares have been bid upwards since the conflict in Ukraine began.

ESG Complications

One significant trends to emerge over the last several years in the financial markets has been the growth of ESG Investing. ESG investing sets environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria as a set of standards for evaluating a company’s investment merits. Fueled by concerns about climate change, social justice and other factors, investors poured a record $649 billion into ESG focused investments in 2021—up from $542 billion in 2020.

The conflict in Ukraine has brought a certain level of introspection around whether or not the defense, nuclear power and fossil fuel industries should be reconsidered in an ESG framework. For example, many ESG funds have had a strict exclusion against investing in companies that provide military equipment. But once Russia marched into Ukraine—the debate has begun whether or not these companies are actually providing a “social good” for a nation to defend itself. As Latvia’s defence minister asked the Financial Times—”Is national defence not ethical?”

Similarly, the debate around oil and gas is less clear from an ESG perspective. A recent study from CIBC World Markets found that some of the largest ESG investment funds in the world held a greater proportion of Russian oil companies than Canadian oil producers in their portfolio due to a wish to limit exposure to the Canadian oil sands. But critics pointed out that while Russian oil companies emit less carbon CO2 per barrel of oil produced, their social and governance criteria is nowhere near as robust. The debate now centers on if and when environmental factors should outweigh social and governance. These are complicated questions with no easy answers.

Shades of Yesterday

Very seldom has history shown that the world makes smooth transitions to an idealized path forward. The promise of the “Build Back Better” agenda has been derailed by war in Europe—something thought to be impossible in the modern world. Conflict in Europe has brought back worries about reliable oil supplies and increased worries about inflation—a relic of the 1970s. The world has always managed to find a way forward—what that progression looks like is obviously unknown. The lesson for investors is that unpredictability is more constant than consensus tends to believe.