The Red Sea’s Inflation Risk

In This Issue:

- Global shipping chokepoints expose risks

- Vulnerability of supply chains exposed again

- Inflation risks are put back on the table

- Houthi militias hold the cards if the Red Sea is going to cause wider economic risks

Over the last several decades, military and shipping industry experts have warned how vulnerable the global economy is to attacks on ocean shipping routes. Nearly 80 percent of all goods are transported by ships and the volume has been growing steadily over the last three decades. From 1990 to 2021, the volume of cargo transported by ships has nearly tripled. from four to 11 billion tons.

The vital importance of the global shipping industry was felt in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Shutdowns in Asian factories, shortages of workers and congestion at ports led to widespread shortages of goods that spurred inflation. The economy was able to put these challenges behind it by the Fall of 2022 and inflation, port congestion and global supply chain challenges all eased.

Global Shipping Challenges…. Again

When armed conflict broke out between Israel and Hamas following the attacks of October 7th, the financial markets were briefly rattled from initial fears of the conflict escalating across the region. Some observers pointed to the possibility of an oil embargo by OPEC nations aimed at reducing oil supplies to North America and Europe. Those worries have thus far not materialized.

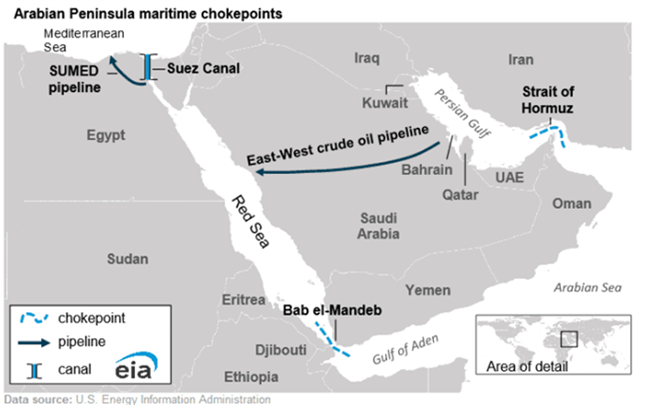

The surprise with respect to the conflict’s impact on the global economy has come from Yemeni based Houthi rebels who receive military training, weapons and technological support from Iran. The Houthis issued a warning to the global shipping industry that any ships passing through the Red Sea that they suspect of delivering cargo to Israel will be attacked. Yemen’s territory borders a narrow 20-mile-wide section of the Red Sea, the Bab-el-Mandeb straits; providing the Houthi militia with an easy reach to target passing cargo ships from their land positions. Perhaps it is no coincidence that Bab el-Mandeb loosely translates into “Gate of Tears” or “Gate of Grief”.

The Red Sea is crucial to the global economy as nearly 12% of global trade flows and 30% of global container traffic passes through it. It is also a key waterway for oil tanker traffic as ships enter the Red Sea to deliver crude oil to Europe and North America via the Suez Canal.

Each year, nearly 20,000 ships travelling in either direction between Asia and Europe or Asia and North America enter the Red Sea and will use the Egyptian controlled Suez Canal. Being the shortest shipping route between Europe and Asia, the route saves approximately 9 to11 days of shipping time and reduces costs that arise mainly from decreased fuel consumption and lower freight insurance costs. If ships are cutoff from this route, then these shipping costs rise and are passed onto consumers and businesses.

Recent comments from Shalanda Young, director of the US Office of Management and Budget, expressed worries about the potential for inflation to rise due to this conflict. Young stated “I worry about the geopolitical space we live in. The Red Sea attacks, shipping, all of these things in the geopolitical space certainty have the chance and opportunity to raise prices ….”

Young was referring to actions of the majority of the global shipping industry that are now avoiding the use of the Red Sea passage and instead electing to sail around the southern tip of Africa. Despite the rise in fuel costs and time, it is seen by shippers as being cheaper than risking an attack through the quicker alternative route given that insurance costs for traveling through the Red Sea have also surged higher. Adding to the complexity of the problem, is that the more ships stuck in travel time creates a shortage of available ships. Whereas a ship might be able to make perhaps six or seven runs yearly, it will now be reduced to four or five runs which can create a global shipping bottleneck.

Inflation Risk Rising

The shipping industry is also warning that possibly global supply chains will once again tighten and under a prolonged scenario, it could result in a shortage of goods available to customers. Scarcity in turn, is a driver of inflation. Memories are still fresh of the supply chain disruptions that caused shortages of cars, electronics and consumer goods in the aftermath of the pandemic. Those challenges took nearly two years to resolve. At this point, we do not believe that the challenges in the Red Sea will exert the same pressure that the pandemic related disruptions did but the more prolonged this threat to shipping becomes, the greater the potential for inflationary pressures from supply chain issues to become an economic hurdle.

In a recent CNBC interview, Alan Baer, CEO of shipping company OL-USA, stated “Given the sudden upward movement of ocean freight pricing, we should expect to see these higher costs trickle down the supply chain and impact consumers as we move through the first quarter.”

In a scene reminiscent of the supply chain challenges after the pandemic, some port congestion issues could make a more muted replay of their performance in 2021 and 2022. Goods from Asia that normally would be destined for the East Coast of the US are being shipped to the West Coast since the cost of shipping to the West Coast is about $2,700 per container while East Coast shipping is $3,900 per container. It is important that trucking and rail capacity be available to move goods from North America’s western ports to their final destinations in the Midwest or east coast. Some retail analysts are worried that clothing fashions for Spring will be delayed – along with furniture, toys and electronics.

Europe in particular has an even more pronounced problem as 40 percent of the trade flows between Europe and Asia flow through the Red Sea. Shipping rates for containers of goods being shipped from Asia to Northern Europe are up 173 percent in less than two months and exceed $4,000 per container.

Weary governments have already felt the anger of voters who are experiencing the pressures of inflation through higher food, fuel and shelter costs. In the US, it is an election year and the last thing any incumbent would want is to face an angry electorate facing rising prices or shortages.

Operation Prosperity Guardian

In recognition of the threat that the Houthi militants pose to the global economy, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin launched “Operation Prosperity Guardian” last month which united the naval resources of the US, United Kingdom, Bahrain, Canada, France, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Seychelles and Spain to push back against the Houthi militants and provide protection for ships. Austin stated that, “The Red Sea is a critical waterway that has been essential to freedom of navigation and a major commercial corridor that facilitates international trade.”

So far, the US military has chosen to adopt a largely defensive posture. While it has successfully shot down numerous Houthi missiles and drones, it has not launched a massive attack on Houthi forces. This is mainly because the US is attempting to avoid an escalation that provokes Iran or other militant groups further involving themselves in the conflict between Israel and Hamas. In late December, the US issued a statement described as a “final warning” to the Houthis but in early January the Houthis responded by attacking another ship. This was a signal that things may get worse before they get better.

Eight Global Choke Points

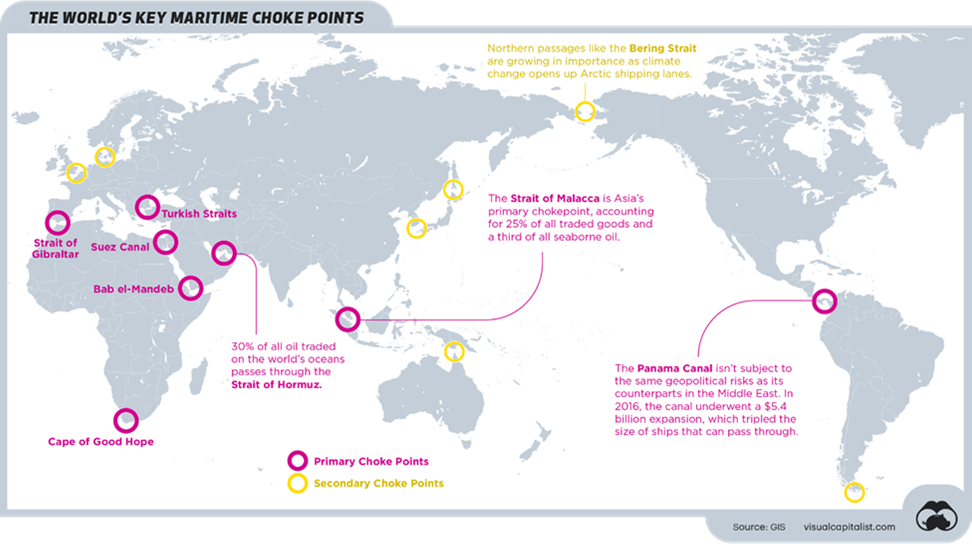

Throughout history, trade ships were seen as legitimate targets of war. Whether it was in the ancient world of Egypt or Greece, during WWI and WWII or even in modern times – ships moving cargo have been seen as valuable strategic targets. Recent events in the Red Sea have reminded the world what some experts have been warning of for the last thirty years, the modern world continues to depend on eight global choke points for maritime trade (see figure above). These narrow chokepoints are all vulnerable to military blockades or attacks by rogue militant groups. As such, any of these corridors would have a ripple effect on the global economy. Choke points are defined as strategic and narrow waterways uniquely located that serve as linkages to other much larger bodies of water. As the figure above shows, the choke points are clearly vulnerable to attacks from armed groups or nations that wish to exert control over a region or a particular nation.

Various geopolitical analysts have noted that China and India – the two most populous nations – import over half of their energy needs from the Middle East. Tankers carrying oil from Saudi Arabia and other Middle East nations have to pass through the Strait of Hormuz which is less than 30 miles wide at its narrowest point. Concerns in the energy market have ebbed and flowed over the last forty years that Iran could shut down the Strait of Hormuz. Under such a scenario, analysts have surmised that oil prices could rapidly double. However, it should be noted that such an act from Iran would invite a strong international response and would most likely involve a military response.

For China, it faces a second choke point for its oil imports as ships must pass through the Strait of Malacca – a chokepoint through which a third of all oil shipped by tanker flows. China worries that it is vulnerable to an energy blockade and is trying to diversify its supplier base of oil by relying on Russia and Central Asia. But for China, even Central Asia carries risks. It is a region that Russia exercises influence upon and it is reluctant to see another nation become too involved in its sphere of influence.

Not Only the Red Sea

An additional challenge to the global shipping industry is coming from the Panama Canal—the second busiest man made shipping lane as it carries about 5 percent of global trade. While the Red Sea and Suez Canal challenges are due to geopolitical issues, the Panama Canal’s challenges are due to low water levels.

Though Panama has one of the wettest climates in the world, the last year has seen rainfall nearing 30% below typical levels. This has caused a reduction in the water levels in the lakes that feed into the canal. The lower water levels in the canal have forced the canal authorities to reduce the number and size of the ships that pass through.

To overcome the reduced capacity, some shipping companies are paying up to $2 million to jump the queue to get through the canal while others are choosing to sail around Africa or South America. Once again, these costs have the potential to raise inflation.

Limited Options

With memories of the last global shipping and supply chain crisis still fresh in the minds of policymakers and consumers, the escalation of the Israel-Hamas conflict to the Red Sea has the potential to once again fuel shortages of goods and higher prices. While the shipping attacks have entered their third month, the global shipping industry has responded quickly to cut its risks. The choice to avoid the Red Sea and instead sail ships around Africa and then onto Europe or elsewhere has resulted in significant costs to shippers who in turn are passing their rising insurance and fuel costs onto their customers. Ultimately, these costs are going to show up in higher prices for consumers.

It is not likely that the events in the Red Sea and Middle East are going to be significant enough to create a 2021-2022 type inflationary wave if the crisis ends in the near future. But the longer this challenge to global shipping remains, the greater will be its economic impact. For their part, policymakers will remain vigilant but they also recognize that when it comes to geopolitical issues that are impacting the supply chains, high interest rates are of limited impact in the inflation battle.