Rising Interest Rates: A Bumpy Road Towards “Neutral”

It has been well over a decade since investors have had to contend with a sustained upturn in interest rates. Even though the US began its march towards the normalization of interest rates almost three years ago from the emergency lows reached during the last recession, investors still seem to have been caught off guard. Anytime the largest economy in the world and the one with the most dominant currency begins to reverse course from a period of low interest rates, there are bound to be some waves.

Perhaps “waves” is understating what has happened in the bond markets and by extension most of the world’s equity markets. Ironically, the US equity market has been the lone island of strength amongst the various international markets. But in contrast, the US Treasury bond index has experienced its longest losing streak (on a total-return basis) since 1976.

In Canada, bond prices have also been under pressure but to a much lesser extent. It is consistent with history that Canada is experiencing direct effects of the US higher interest rate policies given the close economic ties and linkages between the two economies. This is while Canada’s economy is saddled with the most indebted households in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) group of 35 countries that it monitors. It can hardly afford a sustained lift in interest rates as many Canadians struggle to make debt payments.

By contrast, US households have done a much better job of shedding debt than their Canadian counterparts. Part of this is also due to the fact that the US economy is growing much faster than in Canada and job growth is plentiful. As we highlighted in last quarter’s newsletter, US unemployment was so low that many companies were having trouble taking on new business or satisfying existing orders due to a shortage of workers. That has the US Federal Reserve’s attention and is causing it to lean into the still emerging inflationary trends. In short, they are trying to head off a scenario in which an overheated economy with rising wages leads to inflation.

First Signs of Trouble

When economists try to forecast the future direction of the economy, one of the variables that they look at is the yield curve to see if it is inverted. An inverted yield curve develops when short-term interest rates rise and become higher than longer-term interest rates; this often signals that the bond market is worried about the economy and is forecasting slower economic growth ahead.

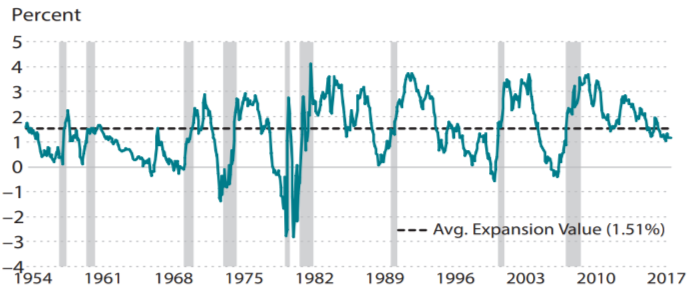

Over the last 64 years, as seen in the Figure 1 below, each time the US yield curve has inverted – a recession has followed. The chart above shows the yield curve using the difference between 10-year Treasury Bonds and 3-month Treasury Bills (we can use other maturities but this is one example) and each time the yield spread between these two kinds of Treasury securities gets below zero (i.e. the curve inverts), a recession has followed. But timing things is a whole other trick because recessions have taken as long as 34 months to appear after an inverted yield curve has taken root.

Figure 1: Treasury Yield Interest Rate Spread (10-year and 3-month)

Source: Federal Reserve Board, U.S. Treasury and Haver Analytics

Note: Gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the NBER.

Some market observers have said that this time is different because interest rates have been so low for so long that the yield curve has lost some of its predictive power. They argue that the reason the yield curve is looking to invert is because the Federal Reserve is pushing up shorter-term interest rates but global investors are willing buyers of longer-term bonds in the US since US interest rates are higher than other developed markets, such as Europe and Japan. As a result, longer-term rates in the US are being anchored. In effect, they believe that the curve is inverting not because of economic worries but because of a lack of opportunities abroad for capital flows.

Taking any one variable in isolation to predict the economy is unwise. Another variable we are watching is the unemployment rate. In particular, we are trying to see if the unemployment rate has put in a bottom and has begun to head higher. If so, it could be a sign that the long feared economic slowdown is finally on its way.

Why Do We Need to Own Bonds Then?

A more-than-fair question investors are posing these days is “Why do I want to own any bonds?” Actually, this question could have been posed with just as much validity two or three years ago too. Only at that time, interest rates were low, bond prices were high and complacency around bonds was high. Investors had become accustomed to low interest rates and low inflation. Even a sharp drop in unemployment still had academics and central bankers scratching their heads as they wondered “Where did inflation go?” Over the last year, things certainly have changed.

One of the most important reasons to own bonds is diversification. It is often said that diversification is one of the few “free lunches” in finance. The purpose of diversification is to reduce risk by owning multiple types of assets such as both stocks and bonds. Historically, including bonds in a portfolio with stocks has provided investors with reduced volatility and a reduction in downside volatility during turbulence in equity markets. Said another way, bonds are added to a portfolio to “zig” when stocks “zag” thereby providing portfolio stability.

When bond prices were stable and the yields offered to investors remained anchored to generational lows, many investors had bought longer term bonds in order to get a higher yield than that offered by shorter term bonds. This strategy worked great as long as interest rates were anchored. As interest rates have risen steadily, US bond prices have fallen sharply. Those investors who paid premium prices for low yielding bonds have suffered double digit losses in a short amount of time.

What Kind of Bonds to Use?

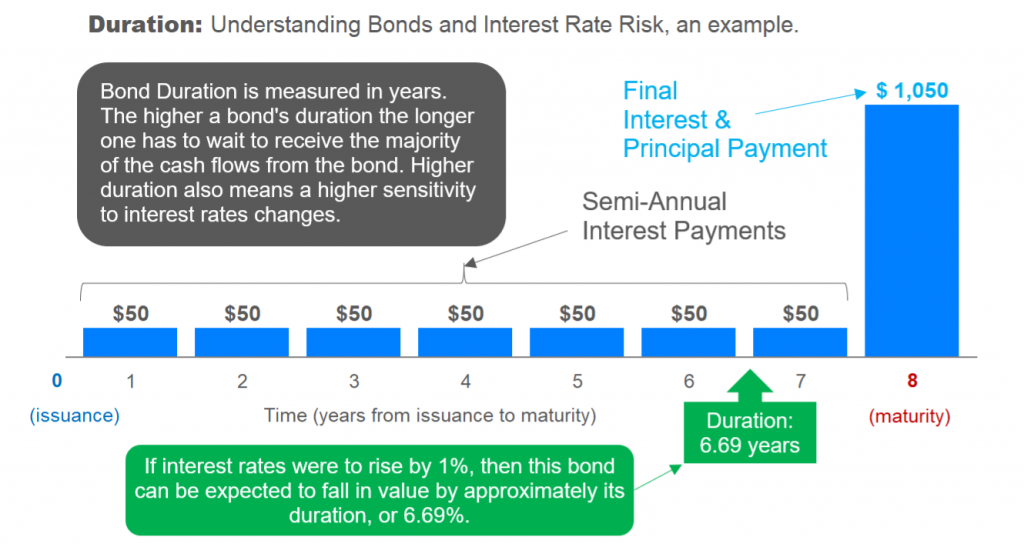

In a rising interest rate environment such as the one we are seeing now, shorter-term bonds are relatively more preferable as they tend to have less price risk than longer-term bonds. The price risk of a bond can be quantified by looking at its duration. As Figure 2 below shows, duration can be thought of as a bond’s sensitivity to a change in interest rates. In an environment with the current interest rate conditions, a low duration bond portfolio will not earn large price gains but it will protect against both equity market volatility and the ravages that higher interest rates inflict on longer-term maturity bonds. At some point, longer-term bonds will once again be attractive additions to portfolios as economic momentum begins to peak. This would allow for the locking in of higher yields and opportunities for capital appreciation.

Figure 2: Bond Duration Example – Understand Bonds and Interest Rate Risk

Is the Fed Putting the Economy at Risk?

Some economists believe that the Federal Reserve does not have much further to go before it can take a pause and use that time to assess the impact of its policies. This is because monetary policy has a lag and sometimes the impact can be delayed or camouflaged.

These economists believe that the rate of economic growth in 2019 will settle back to a more neutral level in the US. However, the consensus is still calling for one more increase in December of this year and three more interest rate increases next year.

The “economy at risk” scenario is based on the idea that the US economy is seeing a temporary boost from the Trump tax cut but this will peter out in 2019. While this remains to be seen, it is clear that as things stand now, global economic growth is once again struggling to maintain its momentum. China and other key emerging markets nations are laboring under mountains of debt and higher US interest rates – which have the effect of pushing up interest rates in other countries around the world.

Trump Tax Cut Complicates Fed’s Task

Like anything else, bond prices are impacted by supply and demand. If there is too much supply (bond issuance), then it can result in interest rates rising as bond issuers have to compete for relatively scarcer investor dollars.

The US budget deficits are providing an example of that today. As the Trump Administration’s tax cut package was enacted into law earlier this year, the fears were that the additional spending measures and tax cuts that formed the 2018 budget would expand the budget deficit. Unfortunately, those fears were well-founded. Despite the fact that the US economy is on its best footing in over a decade and unemployment is about as low as it will get, the most recent data from the US Treasury department shows that the budget deficit actually increased by $113 billion to $780 billion. While revenues were up by $14 billion, spending increased by $127 billion.

When any government runs a deficit, it has to go out into the financial markets and borrow the shortfall (sell bonds to investors) to cover its spending needs. In this case, the US increases the supply of Treasury bonds available. Given the tax cuts, markets have come to the conclusion that there will be a steady supply of bond issuance from the US government. At the same time that the Fed is raising rates, it is also winding down its policy of bond buying that was designed to help keep interest rates pinned down.

One other factor raising interest rates is that foreign governments, such as Russia and China, have been selling their substantial holdings of US Treasury bonds. This results in still more supply of bonds hitting the markets.

How Far Will the Fed Go?

When the US began raising interest rates in December 2015, the markets were calling the Fed’s bluff and did not think they would go beyond a few token increases. Now investors have gone full circle and are wondering when will the Fed stop. To answer that question, economists say that the Federal Reserve would like to see interest rates get to a “neutral” rate where they are high enough to apply some brakes to the economy but not so much as to cause it to lose too much momentum. In a recent interview with PBS, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell explained that the extremely low interest rates were no longer needed as they were “…not appropriate anymore. Interest rates are still accommodative, but we’re gradually moving to a place where they will be neutral. We may go past neutral, but we’re a long way from neutral at this point, probably.” Clearly, the Fed is not willing to change its course anytime soon.