Inflation: Still Not That ’70s Show

In This Issue:

- Supply chain issues hitting the economy

- Inflation concerns rise

- Energy prices throwing a curveball

- All eyes are on the central banks

The emergence of the global economy from the pandemic induced lockdown last year has brought about more than a few curveballs. The turbocharged economic growth rate that began with the end of the economic lockdown 18 months ago has begun to slow down. That exuberance has been replaced with worries about inflation and the global supply chain which has seen a perfect storm of shortages in labor, energy, lumber, semiconductors, shipping containers and for some nations – food.

Effects of the Pandemic & Lean Inventories

The global supply chain refers to the interconnected networks of factories and businesses that span across the world to deliver goods and services to consumers. Policymakers were caught off guard by the suddenness of the unravelling of the supply chain. The main contributors to the effects we are seeing today relate to the disruptive impact of the pandemic, the practice of companies maintaining very lean inventories prior to the pandemic and shortages of energy and labor.

In the 1980s, corporations began implementing the use of just in time (JIT) manufacturing. JIT requires companies to order parts for their production processes as they need them. The rationale was that this resulted in a more efficient use of capital, lowered costs and boosted profits. But what could not be foreseen was a once-in-a-century storm that caused a shutdown of the global economy that shocked the global supply chain. Thus, the pandemic exposed JIT’s weaknesses in the most glaring way.

In the immediate aftermath of the economy’s lockdown, news headlines focused on the global auto industry and the impact that the shortage of computer chips was having on its ability to produce cars and trucks. As the pandemic initially set in, the world’s automakers had axed orders for computer chips to keep inventories lean as they expected demand would take some time to come back. Instead, demand came roaring back – fueled in part by low interest rates, government stimulus and strong consumer balance sheets. Thus, they got caught flat footed and are still playing catch up over a year later.

The global auto industry is expected to see sales fall by $210 billion this year due to the shortage of computer chips as it will not be able to produce enough vehicles for consumers. This estimate is up 90% from earlier estimates – showing how stubborn and unpredictable the shortage of computer chips has been. Consulting firm Alix Partners has stated that it expects global production of autos to fall by 7.7 million vehicles in 2021 – nearly double its earlier estimate several months ago. This has caused inventories at auto dealers to fall sharply and auto prices to hit a record-average price in many nations. Underling the shortage of vehicles is the fact that some auto dealerships have had to rent cars to put in their showrooms for display purposes.

Initial optimism about how long the shortage of semiconductors would last has been replaced by a more pessimistic tone. Last month, Volkswagen CEO, Herbert Diess, said “Probably we will remain in shortages for the next months or even years because semiconductors are in high demand… It will be probably a bottleneck for the next months and years to come.”

Exposing Linkages

While the supply chain crisis began to be noticed with the shortfall in the supply of semiconductors, it has spread. At the center of the global supply chain challenge is the shipping and ports industry. Almost as soon as the economic lockdown ended for much of the world in Spring 2020, shipping rates for cargo ships transporting containers began to rise. At the time, it was thought that this was a temporary surge that would work itself out. But as unpredictable as the pandemic has been, so has the crisis in the international shipping industry.

Earlier this spring, the world watched as a 400m (1300 ft) long container ship became stuck in the Suez Canal, which is the quickest navigational route linking east and west and through which about 12% of the world’s cargo is transported. As a result, ships destined for ports around the world were prevented from moving. This began what was the initial revelations of how interconnected the world is and how a problem in one local area can send shockwaves throughout the world.

But the challenges in the Suez Canal were only a warm-up. As consumers around the world emerged from the lockdown, the demand for goods of all kinds exploded higher. At the same time, millions of shipping containers — the building blocks of sea cargo — were scattered around the globe since they were previously used to deliver face masks, gloves and medical supplies during the initial onset of the pandemic.

Congestion at the Ports

Exacerbating the shortage of containers are delays in unloading cargo at ports around the world. These delays have meant containers are unable to make their way back into the supply chain for reuse.

The delays in unloading were caused by a confluence of factors – ranging from port employees staying home to slow the spread of the pandemic to China shutting down the world’s third largest port in Shenzhen for several weeks due to a single employee found to be infected by the COVID-19 alpha variant. This left dozens of ships with no choice but to drop their anchors and wait for the port to reopen. This shutdown was China in effect putting the world on notice that it will not tolerate the slightest infection count amongst port workers and therefore, port shutdowns are not a “one off.” According to Sultan bin Sulayem, chair of DP World – one of the world’s largest container port operators – “China will not tolerate or allow any opportunity for this (virus) to spread. So, if they have an infection, they close the port — and that reflects in the supply chain.”

No Easy Solutions

The congestion challenge is also complicated by the fact that warehouse capacity is limited for the storage of imported goods. Once containers are unloaded from the ships to free them to return to service, the supply chain is suffering from a shortage of truck drivers and trucks to move the offloaded goods to their ultimate destination. The shortage of truckers is a demographic challenge as the average age of a US truck driver is 58 years old and the work is challenging and often requires long hours.

Likewise, the railway companies are unable to help very much as they too are dealing with not enough personnel or railcar capacity to match the volumes at the ports.

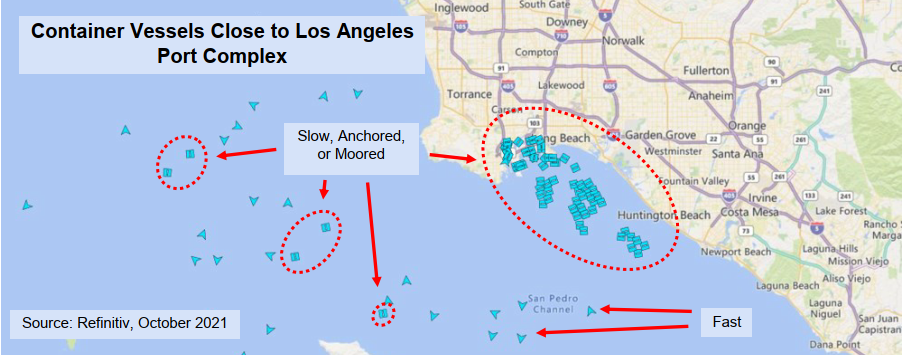

The figure above shows the backlog of ships converged offshore California—waiting to be unloaded. The Los Angeles Port Complex (ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach) is the busiest container port system in the US and handles nearly 40% of all container imports and 30% of all exports.

Energy Supply Shocks

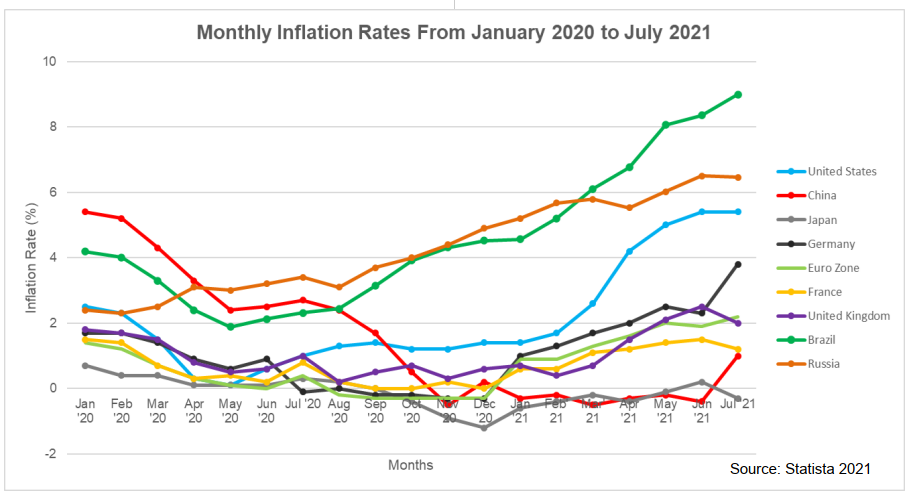

It is not only ports and shipping seeing supply chain issues. The global energy supply chain is also seeing a historic level of impact as the economy rebounds from the pandemic and energy demand has skyrocketed. Despite most of the world’s nations united in their desire to see a reduction in the use of oil, natural gas and coal, fossil fuel prices have staged a furious rise. The price rise has created an energy price shock that is further complicating the inflationary outlook for the global economy (see figure below). While the global economy is less reliant on energy than in the 1970s, which was the last time the world saw an energy supply induced price shock, the risks of the shock leading to inflation are rising.

As governments try to reduce their nations’ reliance on fossil fuels, they are finding that the transition has been met with a hard reality brought about by a confluence of events ranging from reduced oil production, shortages of natural gas, the flooding of coal mines in China and a lack of wind to produce power from offshore wind farms. What governments are learning belatedly is that curtailing fossil fuel supply without an adequate and reliable supply of alternative energy is a recipe for policy disaster.

In Europe, historically low inventories of natural gas and supply curtailments from Russia and Holland have caused natural gas prices to rise by over 500% while energy production from renewable sources, such as offshore windfarms, has fallen due to a lack of wind. In the UK, where wind power production has fallen sharply, natural gas has been accounting for nearly 45% of electricity production while some coal plants have been busier than they have been in several years. It is expected that the surge in natural gas prices will continue even after winter has passed.

Central Banks Being Squeezed

One of the worst predicaments for a central bank is to be forced to deal with an inflation scenario brought about by too little supply. A central bank cannot make more computer chips appear, increase the supply of energy or help ease port congestion. In the 1970s, central banks were too timid in dealing with the inflation that was in part induced by higher energy prices. It is expected that the Bank of England might be the first major central bank to raise interest rates in December of this year. Markets are pricing in a near certainty of a hike in interest rates – up from 45% only two weeks ago.

In recognition of past historical errors by central banks, the Bank of England’s governor, Andrew Bailey, stated that “Monetary policy can’t solve supply-side socks. What we have to do is focus on the potential second-round effects from those shortages.”

In the US, chairman of the Federal Reserve, Jerome Powell has shifted his language on inflation. No longer does he refer to it as transitory. In late September, Powell told a European Central Bank panel that “It’s also frustrating to see the bottlenecks and supply chain problems not getting better—in fact at the margins apparently getting a little bit worse. We see that continuing into next year probably and holding inflation up longer than we had thought.”

The challenge for central bankers is to figure out how to respond to the rise in prices. If they get too zealous and raise interest rates in response to what might be a temporary phenomenon of shortages and supply chain constraints, they could slow the global economy and cut short the rebound from the pandemic. Conversely, if consumers come to expect price rises to be a permanent feature in the economy, they will demand higher wages—setting off a wage-price inflation spiral.

For over a decade, central banks have tried everything to get inflation to rise. It seems that the pandemic and its aftermath have for now solved that problem. Now that inflation is here, those same central banks must figure out how to deal with it.