Inflation Starting to Stir

In This Issue:

- Vaccination rates are the key to maintaining economic momentum

- Government support payments have helped create a surge in household savings

- Pent –up consumer demand could create inflationary pressures

- Global supply chains leading to production challenges for some industries

COVID-19 has had the world in its grip for over a year. A year ago, it was considered a near impossibility that a vaccine could be ready before the end of 2020 but science made the seemingly impossible a reality. The vaccines have allowed the world to focus on the “beginning of the end” in the fight against the pandemic. As the vaccines are distributed and in time immunizations rise across populations, the financial markets are looking forward to a post-COVID world.

On the economic front, the battle against the pandemic has been fought with previously unimagined amounts of stimulus in the form of monetary policy and fiscal policy. With respect to monetary policy, the slashing of interest rates helped to reduce the cost of borrowing and has allowed households to refinance mortgages, buy a new home or purchase a car. For businesses, it has allowed them to borrow at lower interest rates to offset the slowdown in the economy that resulted from the lockdowns. But with interest rates that were already near 0% in Europe and Japan and quite low elsewhere – lowering them further was never going to be enough. To that end, central banks leaned on asset purchases (buying up corporate and government bonds); in turn, this allowed the central banks to put money into the banking system as it paid for those bonds. The intent was for that money to begin circulating its way through the economy.

While the central banks were borrowing from their experience in dealing with the 2008-09 financial crisis, the sheer volume of monetary stimulus today far exceeds what was done over a decade ago. These asset (bond) purchases are what the media refers to as money printing. In 2008-09, many economists and investors feared central banks were going to cause inflation through this policy action. However, the fear turned out to be un-founded as the money printing mechanism was weak-ened by the fact that the money unleashed by central banks was hoarded by banks wanting to strengthen themselves after the financial meltdown rather than aggressively lent out to households and businesses. When the global economy came to a screeching halt in early 2020, the global banking system held up far better than it did in 2008-09 –partly as a result of the regulatory requirements on the banks to strengthen their ability to withstand future crises. The pandemic certainly tested the banks and the financial system and for the most part, it held up amazingly well across the world.

Governments Much More Active

Another reason that inflation did not come roaring back after the then record amount of stimulus after the 2008-09 crisis was because government spending did not measurably increase. In fact, many governments went into austerity mode to try to cut their budget deficits. This watered down the stimulus effects of the policy response in 2008-09.

However, that was then and this is now. An important difference between “then and now” is that this time, fiscal policy consisting of tax cuts, tax deferrals, direct cash payments and increased spending is being used – along with central banks using a supersized version of the 2008-09 monetary policy to support their respective governments. As impressive as the stimulus efforts have been, it is likely that more is needed to give the global economy sustained momentum. Therein lies the challenge—how to continue supporting the economic recovery without firing up inflationary pressures.

Pressing the Fiscal Policy Accelerator

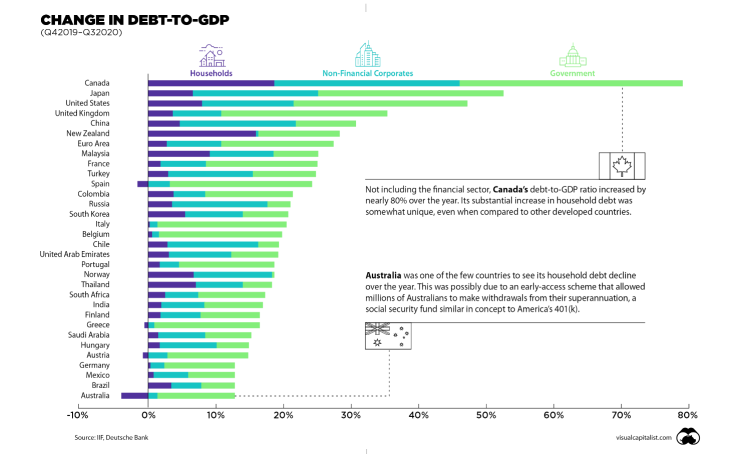

As the data in the chart above shows, trillions in debt has been taken on by households, businesses and governments. With respect to government borrowing, Canada’s government has led the world as its debt –to-GDP level more than doubled. Canada will run a $400 billion deficit for the current year amounting to 25% of GDP. For comparison, the next largest budget deficit as a percent of GDP is the United Kingdom at nearly 15% and the US at about 12%.

The US has enacted about $4 trillion in stimulus to help the US economy shake off the effects of COVID-19 on the economy. This is equivalent to 20% of its total GDP. Of this $4 trillion, $900 billion of stimulus was passed in late December 2020. This last round will see $465 billion given to individuals in the form of $600 direct payments and an additional $350 billion in jobless benefits while the remaining balance is to be spent helping nations in Europe and Asia. President Biden has said the $900 billion is a “down payment” and aims to enact another $1.9 trillion in additional spending for early 2021 – including another $1400 in payments to individuals.

In Canada, Statscan data shows that household income (private-sector earnings) fell by just one per cent ($15.2 billion) to $1.52 trillion between the first quarter and third quarter of 2020. But transfers from government, which include existing programs such as employment insurance plus new coronavirus-era programs, made up for that drop many times over. Those transfers rose by $103.8 billion from the first quarter to the third quarter, meaning that the government effectively gave households nearly $7 for each dollar of lost private-sector income.

It is not a certainty that the incoming Biden Administration will be able to get its proposal enacted as senators from both parties are starting to sound the alarm on spending. For example, the additional $1400 payment to individuals would raise government spending by an additional $463 billion. Government transfer payments made up 35% of total US disposable income (after-tax personal income) by mid 2020. In fact, the amount of money from the federal government that has gone to US households exceeds the losses from the economic downturn according to data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve. US households are flush with savings, which have risen by over $1.3 trillion since the pandemic began and are waiting for the skies to clear so that they can resume vacation travel, restaurant visits, trips to the movies and so many other things that have been curtailed due to the pandemic.

Pent-Up Demand

As the initial lockdown ended in the latter part of last spring, US households went on a spending spree reflecting pent-up demand. Similarly, after the Spanish flu pandemic ended in 1919, the US economy saw a surge in pent-up spending activity that kicked off the roaring ‘20s. The financial markets are looking to 1919 as a potential playbook for what happens in 2021. To say that an effective vaccination strategy is the key to the economic recovery is an understatement.

Restaurants could provide an example of how pent-up demand could lead to a rise in inflation. Across North America, many restaurants have closed permanently. If there is a sudden surge in demand for dine-out experiences, the remaining restaurants will be able to raise their prices. Economists expect that as restrictions ease with more vaccinations, the service-side of the global economy will come roaring back. In addition, the same will apply to the manufactured goods side of consumer spending. An economy that has fully emerged from hibernation and lockdown will see a rise in demand for everything from clothes to furniture.

Supply Chain Disruptions

Unlike in the 2009 economic recovery, which was led by a resilient service side of the economy, the 2020 economic recovery has seen a huge rebound in manufacturing. As 2020 began, the US and China had barely finished the signing of the US-China trade agreement. Leading up to the agreement, many manufacturers had let their inventories run down due to uncertainty around the question of whether or not an agreement would be reached or if there was going to be a trade slowdown that would end up hurting the global economy. No sooner had the agreement been signed that the COVID-19 pandemic threw the global economy into a deep freeze.

The importance of China’s role in the global supply chain was highlighted in early 2020 when its lockdown forced the abrupt closure of many factories. More than 200 of the 500 largest companies in the world have a presence in China’s Wuhan province, which was believed to be the center of the COVID-19 outbreak.

In response to this sudden economic shock, many manufacturers in vitally important industries such as auto parts and semiconductors – amongst others – began to shutdown. In recent weeks, the global automotive industry has announced delays in the production of certain vehicles due to a shortage of semiconductors. In order to better ration the semiconductors, the auto industry is shutting production of smaller vehicles in order to keep their luxury and SUV production lines going. This is where the weaknesses in the global supply chain are starting to become apparent. There is likely to be a shortage of certain manufactured goods and if demand is sudden and strong as vaccinations are performed, there will be an increase in prices due to the supply shortfall. When the restrictions were eased by late spring last year, many manufacturers were met with a surprisingly strong wave of buying and unfilled orders. In the first half of 2020, US auto sales were down by 34% but finished the year down only 15% as car buying surged unexpectedly.

While the semiconductor industry is responding to these challenges, it is expected to still take six to nine months for semiconductors to make it to the auto manufacturers and the automakers are still not seeing the volumes they need to get production up to full speed.

At this point, if there is a prolonged shortage of new vehicles, the inflationary effect would be to raise the prices of used cars and the prices of certain new cars and trucks. This should not be worrisome from an inflationary perspective since it will be seen by policymakers and the financial markets as a temporary phenomenon.

Inflation fears are starting to heat up. Officially, the data for most of the developed world shows inflation is still below the 2% goal that most central banks are working towards. But beneath the surface, we are seeing double-digit price increases for certain good and services. With some exceptions, the reason for these sharp price rises is due to supply of certain goods being reduced as global supply chains have been disrupted by the pandemic.

Vaccination and Inflation

As government stimulus continues into 2021 and vaccination rates rise, the global economy is expected to accelerate. The challenges to the supply chain of the global economy is going to cause shortages of certain goods and price increases in others. Some of the pricing pressures will fuel temporary increases in inflation and some upward pressure on interest rates in the bond market. Over the intermediate term, governments will have to balance their support for the economy with the risks of fueling inflation and begin focusing on ways to start paying down some of their debt load.