China’s New Normal

In This Issue:

- China’s economic challenges

- China real estate sector causing significant disruption

- China’s population expected to fall 50 percent by the end of this century

- Implications for the global economy

Over a decade ago, many scholars and commentators had concluded that China’s economic rise would mark this century as China’s to achieve a level of global dominance. Observing China’s economic growth rates, the expansion of its military capabilities and its increasing reach across the world—it was a plausible, and for some, a foregone conclusion.

In 2009, British journalist Martin Jacques wrote a widely acclaimed book titled “When China Rules the World: The End of the Western World and the Birth of a New Global Order”. His premise, geopolitical power was shifting towards China given its rapid economic growth powered by a huge population, a government able to steer the nation’s resources to its aims and a western world that had “peaked” by standard measures. Jacques was not alone in his thoughts and the bet on China’s unstoppable rise seemed to be a wise one – at least on paper.

Maturing Economy

There is no doubt that China’s economic rise and corresponding clout around the world has been rapid and significant. Few nations in history have risen as quickly and to the heights that China has advanced. Data from the World Bank shows that over the last 40 years, China’s economic growth has lifted nearly 800 million people out of poverty. For clarification, the World Bank defines poverty as $1.90 USD of income per day.

Decades of very strong economic growth have allowed China to become the second largest economy in the world. Expectations were that before long, the Chinese economy would surpass that of the United States. However, recent economic data has put that assumption largely to rest. Where China was regularly growing its economy by 7 to 9 percent annually (a rate that allowed its economy to double in size every 8 to 10 years) more recent data has shown that the Chinese economy is officially growing in the range of 4 to 5 percent.

While this rate of economic growth is still substantially higher than what the developed world is able to achieve, it is worth noting that China’s official economic data has been questioned for its quality (accuracy). A small minority of economists have long said that China’s economic data overstates its economic growth rate by 40 to 60%. A 2017 study by the St. Louis Federal Reserve found that China’s economic data had gotten better but its“ economic statistics remain unreliable.” The St. Louis Federal Reserve’s study found economic data “falsification at the provincial and individual levels as the biggest source of unreliable GDP statistics.” Data falsification is thought to occur in rural areas where leaders are evaluated by the economic performance of their local jurisdiction. In turn, GDP measurements and other economic statistics get inflated at the provincial level.

Another method to evaluate the quality of China’s economic data has looked for growth consistency in China’s energy consumption. A growing economy should see energy consumption rise with economic output. University of Pittsburgh Economist, Thomas Rawski, found China’s energy consumption to be out-of-step with its economic growth rates.

Admitting to Challenges

Official economic projections from the Chinese government point to economic growth of about 5 percent this year. When the government released this estimate, it caught many by surprise as it was seen as a rare admission by China that its economy is troubled and the post-pandemic restart will be labored.

Several factors are hobbling China’s economy; First and foremost, is the decline of China’s real estate sector. For many years, contrarians who looked at China’s economy worried that its real estate market played a dangerously significant role in its economy. Since economic reforms first began in the 1970s, China’s real estate market has been a central force in pushing economic growth higher. The estimates for how much of China’s economy is tied to real estate vary widely but they range from 17 percent to a high of 29 percent as cited in a research paper by Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff. Rogoff also determined that the real estate and construction sector accounted for 15 percent of urban employment in recent years.

Herein lies a big problem for China’s economy; China’s real estate developers, which are some of the largest companies in China, are carrying hundreds of billions of dollars of debt. Meanwhile, its government is trying to implement policies aimed at downsizing real estate’s influence on the economy. A formidable challenge for China’s government that is analogous to walking a tightrope.

Thus far, the government’s policies are having a chilling effect on the economy and the real estate sector. Last year, Evergrande – China’s largest developer – defaulted on nearly $130 billion of its $300 billion debt load. Less than two years ago, Evergrande had owned over 1300 real estate projects in 280 cities in China. Evergrande is not alone. Other developers who were thought to be safe have rattled the Chinese economy by missing debt payments.

If Rogoff’s estimate of the real estate sector are correct, China’s economic path is likely to be a turbulent one. The problem for China’s real estate sector began even prior to the onset of the COVID pandemic. Property developers had become used to making enormous profits from the multi decade real-estate boom that swept across Chinese cities. In the decade prior to the pandemic, Chinese real estate sales were growing at an annual rate of nearly 22 percent! Fueling this boom was easy credit—leaving developers owing over $5.5 trillion USD to lenders.

Reining in Real Estate

Alarmed at this enormous build up of debt, the Chinese government introduced some tough measures and began to restrict the flow of credit to developers. The government has stated that the nation must “embrace a new normal” that relies less on fixed investment (construction fueled by speculation) and instead rely more on consumer spending and technological innovation.

China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) went so far as to label the escalation of debt in the real estate sector as “reckless”. To its credit, China’s government understands it has a problem and is facing it. But the task of trying to fix it is not going to be easy.

Lacking Resiliency

If one were taking bets in the spring of 2020 as to which nations would lead the economic rebound from the COVID recession, a safe bet would have been China. That bet would have been very wrong.

Whereas western nations decided to employ enormous stimulus through government spending and ultra-low interest rates, China chose to stimulate less for fear of firing up its real estate sector which it was trying to slow down. In addition, China was reluctant to admit its zero-COVID policy was an error and change course. It was not until massive protests erupted to challenge the enforced draconian lockdowns that the government relented and relaxed its measures.

Post lockdowns, the thought amongst investors and economists was that the Chinese economy would come roaring back. This theory was based, in part, on the memory of economic growth after the 2008 recession. In reality, the post pandemic global recovery has been US led with some assistance from Europe and Japan.

Normally, when an economy slows down, the policy fix involves increased government spending and lower interest rates to stimulate the economic rebound. But China’s policymakers have resisted this urge. The government has so-far adhered to their long-term plan to shift the economy towards one that is powered by consumer spending and technological innovation.

Technological innovation is an extremely urgent national priority for China. The government sees its reliance on superior western technology as a strategic vulnerability that leaves it at the mercy of North American and European governments. One of the few things that unites politicians in the US over the last decade has been a desire to be tougher on China and restrict access to US technology. The US sees its technological superiority as a strength that will limit China’s future power and keep its military from being able to mount a credible threat to its interests. The European nations are also largely united behind this goal. In recent weeks, Germany has announced policies aimed at limiting China’s access to German research and development conducted by its academic institutions and corporations. The UK and EU have stated that relations with China have become “imbalanced” – which is diplomatic code for “overreliance on a China that might not be an ally.”

Aging Society

If real estate is a challenge for China, its other problem might be insurmountable. Earlier this year, China’s population was surpassed by that of India (four years earlier than earlier UN projections) as China’s population has begun to age rapidly. By 2035, it is estimated by demographic experts that China will have about 402 million citizens who are 60 years of age or older. Currently, this age group is estimated to number at about 255 million.

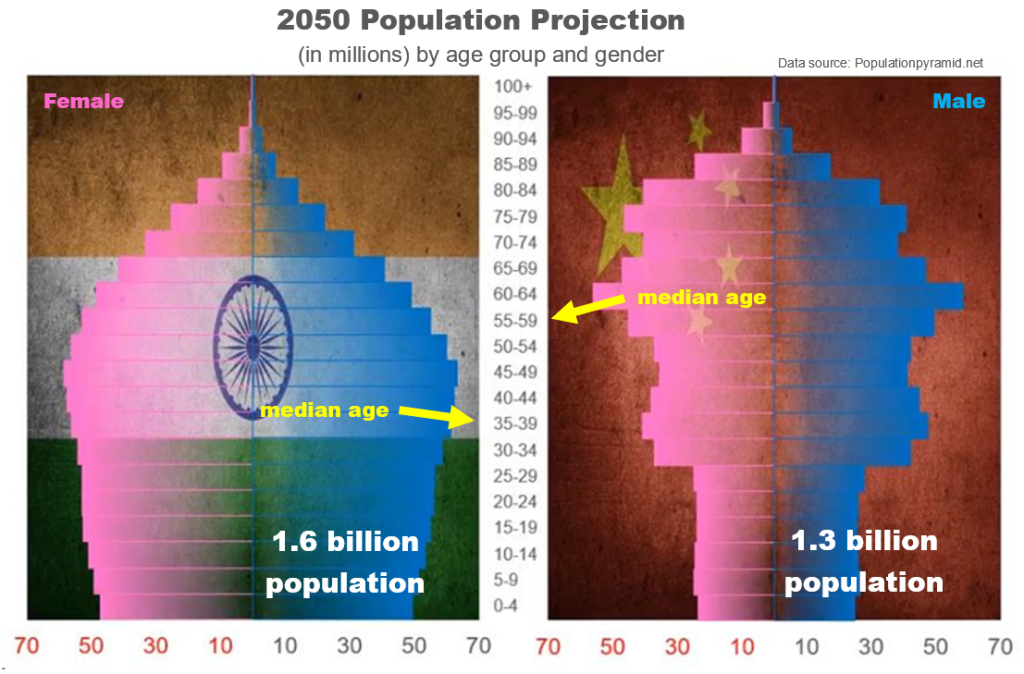

As the chart shows, China’s population is projected to be much older than India’s with a greater tilt towards males outnumbering females. Other data from China shows that men outnumber women by 32 million. The figure also shows how a large elderly population in China will have to be supported by a relatively smaller working age population.

China’s population decline has its roots in the one-child policy introduced in the early 1980s and kept in force until 2016. The Chinese government is now incentivizing families to have more children but it has had little impact. Other nations such as South Korea, Japan and Russia have also tried financial incentives to help stem the population decline of their respective nations but it has had very limited success. The base case projections envision China’s population dropping to drop to about half of its current level by the end of this century.

Shrinking Workforce

As China’s population ages, its workforce has begun to shrink. In the last 3 years alone, China has lost 41 million workers who are no longer in the workforce. For comparison, this is roughly the size of the entire workforce of Germany. Not all of this is due to demographic challenges. Some workforce shrinkage is due to a slowing economy and many workers unwilling or unable to return to work following the pandemic.

An economy can only grow if it has a rising supply of workers who are increasingly productive through technology and improved production processes. But current data shows that many foreign firms are finding it challenging to operate in China as skilled labor is hard to come by. In addition, the current scarcity of skilled labor has increased labor costs—causing Western firms to find other countries to relocate their once China-based production.

China’s Challenges

The financial markets have been expecting China’s government to buckle and abandon its tough measures aimed at slowing down its economy and letting its real estate sector go through a tough restructuring. So far, the government has not flinched. But it has made friendly comments aimed at Western corporations that state China can pursue its national aims while working with western companies that invest in China.

For the rest of the world, when the world’s second largest economy enters a sustained low growth mode there will be long-term negative implications for global growth.

Though China backtracked on zero-COVID policies after its citizens erupted in anger, it is showing no signs that it is willing to relent on its real estate sector. It sees the sector as a potentially destabilizing force and the one thing the Chinese government will not tolerate is instability. The problem is that the road ahead is going to be a long one. An ageing society, a real estate sector that needs a tough restructuring and a government sending mixed messages about its commitment to the path of capitalism are showing that China’s road ahead will be a challenging one.