Canada’s Challenge: Closing the Productivity Gap

In This Issue:

- Canada’s economic malaise

- Caught in a population trap

- US economy sets the productivity bar

- Rising population and labor supply will not bail out Canada from its challenges

The story of major economies of the world undergoing a prolonged period of malaise is more frequent than it might appear. Japan’s economy was once regarded as the miracle economy as it went on a nearly 40-year charge upwards after WWII. For the last 35years, Japan’s economy has been tied to the phrase “The Lost Decades”. In the UK, the 1970s were a time of social and economic upheaval as the nation’s economy became inundated with labor strikes, unemployment, inflation and the inability of its products to compete on the world markets. The UK was in such dire straits that even the Soviet Union viewed British goods as inferior. A declassified conversation between President Gerald Ford and Henry Kissinger quoted Kissinger as saying “Britain is a tragedy – it has sunk to begging, borrowing, stealing…That Britain has become such a scrounger is a disgrace…”

Not longer after this conversation took place, Ford’s successor, Jimmy Carter told the US in a national address in the summer of 1979 that the American people had lost faith in the ability of the government to fix the problems the US faced. He stated “A majority of our people believe that the next 5 years will be worse than the past 5 years. Two-thirds of our people do not even vote. The productivity of American workers is actually dropping, and the willingness of Americans to save for the future has fallen below that of every western nation.” Initially, the speech was well received for its honest and frankness but as conditions continued to deteriorate and confidence sank further, the speech became known as the “malaise” speech.

Northern Malaise

Looking at the contents of Carter’s speech, it could be used to describe Canada’s current predicament. For the last several years, it has been our contention that a malaise has been setting in across Canada. A poll taken at the start of this year showed over half of Canadians want an election as soon as possible or later this year. Another poll taken in late 2023 by Pollara showed that only 31% of Canadians are optimistic about the future of the middle class and only 52% are confident their children will be part of the middle class or higher.

Polling data and economic trends show that Canadians’ confidence about the future can be tied to their inability to get ahead of rising household debt levels. At the end of 2023, Canadians’ household debt was 101.2% of the year’s nominal GDP. In the G-7 group of nations, only the UK comes close to Canada at 85% with the US down at 64% of household debt to nominal GDP.

To further underline the national mood of Canada, consulting firm Meredith and Boessenkool Policy Advisors found that over 60 percent of Canadians believe that “Canada is broken.” The factors behind this shocking number are related to the cost of living, housing, health care, immigration, public safety and lack of confidence in the government itself.

Rising Debt, Stagnant Income

High levels of debt can be overcome in time with the right set of macroeconomic policies that boost economic growth, raise employment and in turn boost household income. Unfortunately for Canadian households, rising debt and stagnant income growth has become a serious challenge. About 75 percent of household debt in Canada is tied to mortgages. The chronic shortage of housing relative to years of rapid population growth has left Canadians scrambling to pay ever higher prices for shelter.

The shortage of housing has reached record levels and current data shows Canada has only one housing start for every 4.2 people entering the working-age population.

Population Trap

Canada’s current population growth has been too fast relative to the ability of its economy to absorb it into the workforce. At the same time, social services such as health and education are becoming policy challenges for governments at all levels to resolve. Earlier this year, Stefane Marion, an economist for National Bank published a report on Canada’s economy in which he stated that Canada has been caught in a population trap. This is defined as a situation in which the population has risen too fast and too quickly and there is not enough capital creating opportunities for the rising population to be absorbed. A population trap has tended to happen in emerging economies—not developed economies.

The lack of productive capital for the Canadian economy and its workers is highlighted by the fact that the capital stock (roughly defined as plant, property and equipment) of the business sector has been declining for seven years and is down to the same level it was at in 2012. Given the Canadian economy has grown in nominal terms by 17% over that time, it means that Canadian businesses have not seen fit to invest in order to expand and update their productive capacity.

Ignoring Impact of Policy

For its part, the Canadian government is highlighting that the economy has recovered the lost ground from the pandemic and GDP has surpassed pre-pandemic levels. Its last budget stated that “Canada’s economy is now 103 per cent the size it was before the pandemic, marking the fastest recovery of the last four recessions, and the second strongest recovery in the G7.”

The government is saying that the size of the economic pie has never been larger – but neglected to mention that each person’s share of the economic pie (per capital income) has been falling for the better part of the last seven years. This is the same length of time as the stagnation of the capital stock. This is no coincidence since workers need updated equipment and productive capacity in order to produce more output per hour worked. This is what economists refer to as productivity.

Productivity Growth is Quality Growth

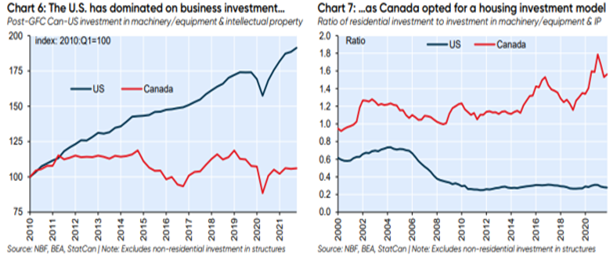

The shortage of housing has been a key contributor to economic growth. High real estate prices have increased construction activity that has translated into economic growth While housing investment is no doubt important for any economy, Canada has become dependent on it and this has fueled a low quality source of economic growth powered by debt. This is diverting capital away from finding its way into investments that will enhance future economic growth.

As things stand currently, both domestic and foreign investors are sending their cash to jurisdictions besides Canada. This reduction in the supply of capital means businesses are competing increasingly against the real estate sector for access to relatively scarce capital. No major economy relies on residential real estate investment for economic growth as much as Canada as real estate accounts for over 20 percent of GDP and over 40% of fixed capital formation. Economists estimate that Canada’s economy is 10% more dependent upon housing than the US was at the peak of its real estate bubble in 2006.

The reliance on real estate for fueling economic growth is a poor quality economic lever. It has actually further undermined future productive capacity as real estate has absorbed a relatively scarcer supply of capital – leaving less for the private sector to retool an ageing stock of productive capital (plant, property and equipment).

Canada needs its companies to invest more in their productive capacity. Such investment is the foundation for future economic well-being because it leads to innovation and the ability to compete on world markets. More investment in machinery leads to more output per worker which pushes up wages and raises the standard of living for a nation. The productivity of labor is important for any nation because it is one of the purest drivers of economic growth since it is an economic lever that produces no significant negative consequences. It is the most desirable way to strengthen economic growth.

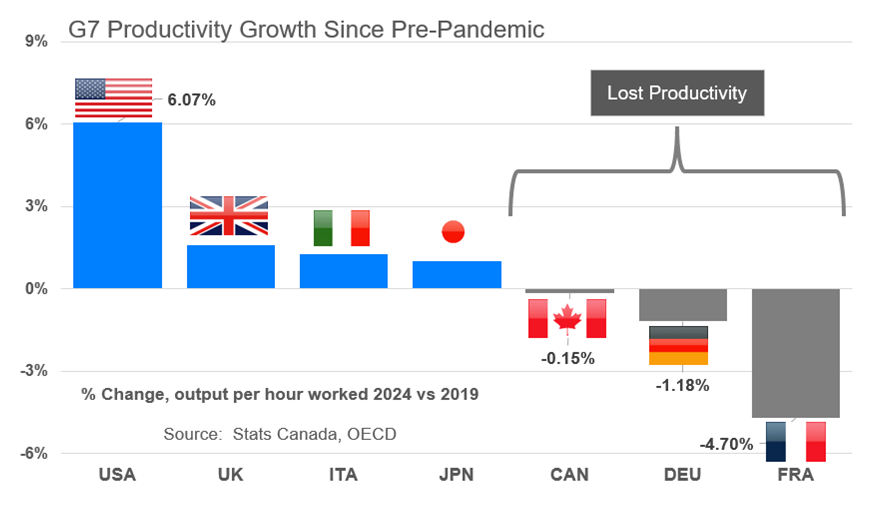

Unfortunately for Canada, its productivity track record is getting worse – not better – even with the spotlight being put on it for the last several years. Its productivity has fallen for 13 straight quarters and is back to 2016 levels and has never had a slower growth rate in labor productivity over any previous eight-year period.

As Chart 6 shows, since the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, the paths of Canada and the United States have diverged widely when it comes to investment in machinery. This is now showing up in the productivity data. The chart on below shows that the US has led the entire G7 group of nations by a wide margin in terms of annual output per hour of worker labor.

The US Sets the Productivity Bar

In 2018, the Canada’s Senate Committee on Banking, Trade and Commerce warned of Canada’s productivity challenge when it stated that Canada was rapidly falling behind the US. It stated that the US had gone from being the seventh most competitive economy in the world to second in only 5 years while Canada remained stuck at 14th.The US economy continues to lead the G-7 group of nations in terms of economic output per worker. Its productive labor force has allowed it to absorb a rising pool of workers – keeping unemployment down – while boosting per capita income. Economists say that a nations per capital income is synonymous with the standard of living.

To provide some additional perspective, the Public Policy Forum – a Canadian public policy organization – stated that in the three decades after WWII, Canadian real weekly wages rose 2.5 percent per year. This allowed Canadian wages to double in under 28 years which set young workers on a path to double their income well before retirement. Such a rise in the standard of living likely provided a sense of optimism about the future – a stark contrast to the mood unveiled by the surveys outlined earlier. But in the last five decades, Canadian real wages have grown by less than a quarter of a percentage point per year. This pace means wages would take 288 years to double!

Canada’s productivity problems long pre-date the surge in its population. Its policymakers made a mistake thinking that a rising population would make up for the shortcomings of its economy arising from taxes, regulatory uncertainty and an inadequate supply of capital that finds more attractive returns in other nations. Canada has essentially gambled that this could be overcome by a surging labor supply through a more welcoming immigration policy. Unfortunately, the labor supply has not helped productivity and that has led to the stagnation of per capita incomes. The data shows that Canada’s long-standing productivity challenge will not be solved with “quick fix” approaches.