Bonds Finally Get Interesting

In This Issue:

- Bond markets are pivotal to markets

- Policy errors destroy bond returns

- Balanced portfolios showing historic declines

- Bond price drop creating attractive valuations

The late comedian Rodney Dangerfield was known for the famous line “I don’t get no respect.” When it comes to investing in the financial markets, bonds often get the Dangerfield treatment compared to the stock market. Bonds are often considered to be boring since they usually offer predictable returns and do not offer the excitement and upside reward offered up by relatively exciting equities. For this reason, bonds are seldom brought up in conversations around the office water cooler or cocktail parties.

The irony of this attitude towards bonds is that the bond market is the most powerful market in the world. The former political advisor to Bill Clinton, James Carville, once stated that if there is such a thing as reincarnation then he would like to come back as the bond market because that would mean he could intimidate everyone. What Carville was alluding to was the power of the bond market to act as the center of gravity for the global financial market.

The bond market’s relevance to all financial markets comes from the fact that it sets the interest rates on every type of borrowing whether it is a mortgage, a car loan or a government’s ability to finance its budget. The bond market sets the direction for interest rates to either move up or down. It is for this reason that central banks are able to use monetary policy to influence the bond market to either help raise interest rates or to lower them – depending on the desired policy goal.

Policy Errors Fuel Inflation

With the onset of the economic crisis brought about by the COVID pandemic in 2020, central banks focused their policies on influencing the bond market to bring down interest rates. They did this by both flooding the global financial system with money (liquidity) and sharply cutting their respective policy interest rates. Unlike during the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, the central banks were aided in their stimulus programs with a torrent of cash payments and tax cuts from governments.

While the policies allowed the global economy to escape the potential of facing something akin to the Great Depression, policymakers now are confronting the downside of those policies which is a forty year high in inflation. Inflation is something that has not been seen in the developed economies for nearly forty years. Clearly, policy makers made an error when they underestimated inflation’s staying power. In one of his first addresses of the year, the governor of the Bank of Canada, Tiff Macklem, stated that “We were faced with the biggest, the sharpest recession we have ever seen in our lifetimes, and we took extraordinary actions. And they have worked. The economy has come back impressively….I’m not comfortable with where inflation is, but I don’t regret the actions we took.”

Macklem is certainly correct in taking a tougher line on inflation but here is the rub – he spent the previous two years reassuring Canadians to continue borrowing as he would not be raising interest rates for some time. Macklem is not alone. Jerome Powell, Chairman of the US Federal Reserve, stated in the summer of 2021 that the early signals of impending inflation “… have been larger than we expected and they may turn out to be more persistent than we expected…the incoming data are very much consistent with the view that these are factors that will wane over time and then inflation then move down toward our goals.” Clearly, the policymakers got inflation wrong.

Only thirteen months later, Powell’s shift could not be more stark. “We have to get inflation behind us. …. We want to act aggressively now, and get this job done, and keep at it until its done.”

Navigating Uncharted Waters

To be fair to central bankers, they could not have anticipated the rapid snapback or surge in demand from consumers; companies overstocking inventory – thereby causing a surge in orders placed with their suppliers at a time when supply chain issues were causing a scarcity of goods; a workforce reluctant to come back to work creating a shortage of labor and resulting in higher wages; the rise of COVID variants with unpredictable economic outcomes and China’s zero-COVID policy and finally – the outbreak of war in Ukraine this year. With respect to the war, while the toll on humanity is incalculable, the financial markets have calculated its ability to impact inflation was fleeting given the current course of the conflict. Not long after the conflict began, markets shifted their focus primarily back to what policymakers will do with interest rates and the ability of the economy to solve some of the inflationary challenges.

Rise of the Bond Vigilantes

Central banks had essentially promised the financial markets that they would not raise interest rate for a long period of time and encouraged households and businesses to borrow and “not worry about interest rates”. However, both borrowers and the central banks either ignored or underestimated the impact of the “bond vigilantes” – a term used to describe bond investors who take matters into their own hands and force interest rates up when they get uncomfortable with the state of inflation or risk to the future returns available to them in the bond market.

These investors exert their influence by selling bonds which causes their price to fall. As their price falls, the bonds offer the same amount of interest income but the new buyers of the bond has to invest less money to get the same return and the original bond owners takes losses. In simple terms, bonds are repriced so the interest income offered by bonds rises and we get rising interest rates that begin to permeate throughout the economy. As if often the case, the bond markets tend to lead central banks in interest rate policy changes.

Bond Investors Seeing Historic Losses

When we look back to the immediate aftermath of the COVID induced economic crisis in 2020, fearful investors ran out of the stock market into the arms of the bond market looking for safety at any cost. They were lured by central banks that had offered a promise of sorts that investors had nothing to fear since they would be buying up bonds for the foreseeable future starting in March 2020. But the problem was bond investors were betrayed by their fears. They were buying the safety of bonds at overinflated prices which meant the yield or interest rate they were earning was too low. Add up overinflated bond prices with a paltry, near zero-percent interest rate and there was an almost guaranteed recipe for losses. As global interest rates in the bond markets began to bottom in the summer of 2020, bond prices started to fall. Bond investors had caught onto the idea that central bank promises to keep bond prices propped up was likely to be taken back and as the economy steadied itself, inflation was going to be a problem at some point.

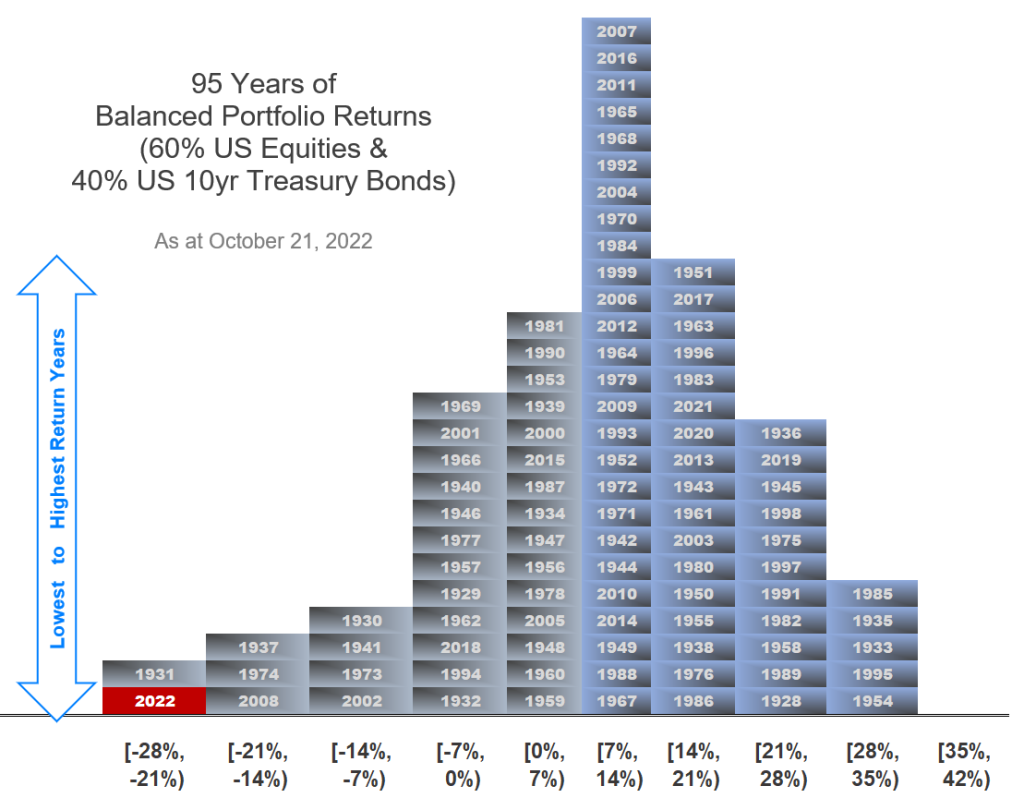

One of the main reasons for owning bonds in a portfolio – along with stocks – is that when the usually more volatile stock market zigs, the less volatile bond market zags. To put it another way, we can say that when stocks fall, the relative safety of bonds should offset the downside of stocks. That is the usual scenario. This year is different as the figure below shows.

Bonds Were Overpriced and Risky

For bond investors, they are realizing that buying overpriced bonds was risky and the safety they thought they were getting has been eroded away. The figure above shows a long-term look at the returns over the last 95 years for a US investor who allocated 60 percent of their portfolio to the US stock market and 40% of their portfolio to a 10-year US Treasury Bond.

We can see that extreme negative returns for an investor balanced in this way between stocks and bonds are very rare. With year-end still over two months away, the chart above shows that 2022 has been the worst year on record for balance investors.

What Went Wrong for Investors?

The balanced investment portfolio return for 2022 shown in the figure above is not reflecting the worst returns in nearly 100 years because the economy is in dire straits where unemployment and misery abounds, as was the case during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Instead, this time the poor return is largely because interest rates were artificially low and that pushed up the value of bonds and that of many speculative companies to an unsustainable level. The excesses that built up are being corrected and investors who embraced the most overvalued investments are paying the biggest price in terms of capital loss.

For bond investors, what went wrong is that bonds had become overpriced (expensive) and the interest rate or yield that they offered was too low. That is a recipe for poor forward returns. Our decision to largely forgo buying bonds for the better part of the last two years was due to these factors.

For their part, too many stock market investors followed the T.I.N.A. narrative – there is no alternative to stocks. As speculative excesses showed up in certain parts of the stock market, many retail investors who had stayed out of the stock market since the downturn of 2008 – along with aggressive institutional investors— poured their capital into the stocks of marginal companies who had poor businesses that were not generating near enough cashflow to justify their stock prices. In many cases, there was no cashflow at all.

In North America, interest rates (yields) in the bond markets bottomed in early August 2020 and began to rise. In the initial weeks and months, this was purely a reflection of a more normalized world economy starting to spring back after the pandemic. But by the following year, central banks began to raise their policy rates and signal to the financial markets that they were starting to take notice of inflationary pressures.

As interest rates rose, the stock market collectively took out its pencil and calculator and began to revalue the future cashflows of companies. The more growth oriented a company is, the harder the markets turned on them. Many companies who had most of their growth expected to come in future years saw their shares fall by over 70% in under a year.

As interest rates have continued to climb and worries about the economy climb, stock market investors have now turned their sights onto mature stable growth companies and have been selling their shares.

Historic Declines Create Opportunities

While substantial stock market selloffs happen once or twice a decade, it is rare for them to happen alongside a rout in the bond markets. The extreme overvaluation of the global bond market that had begun with the onset of the of the pandemic in 2020 has undergone a historic correction. For the first time in over a decade, investors can attain bond income that is meaningfully accretive.

Though it is hard to see given headlines and our own respective experiences as consumers, the early indications of peaking inflationary pressures have begun to appear. Decreases in supply chain constraints and more companies seeing a fall in cost pressures from suppliers are signals that the inflation genie is finally ready to go back into the bottle—albeit at an uneven pace.

Recession Fears Linger

The biggest question on the minds of investors is “When will the recession be here?” At this point, some of the leading economic indicators are leaning towards a slowdown. Investors have begun to price such a scenario into stock prices to reflect a fall in corporate profits in response to a slowing economy. Thus far, even with one of the most aggressive policies of raising interest rates by the central banks, the global economy is faring better than might be expected.

Stocks tend to bottom while the economy is still in recession as markets discount the future recovery and begin their ascent. Of the last twelve US recessions, stock markets bottomed and rallied by over 25 percent before the economic pain of a recession was over. History and experience offer reasons for optimism.