Banks Create New Hurdles for Economic Growth

In This Issue:

- The 2020s nothing like the Roaring 20s

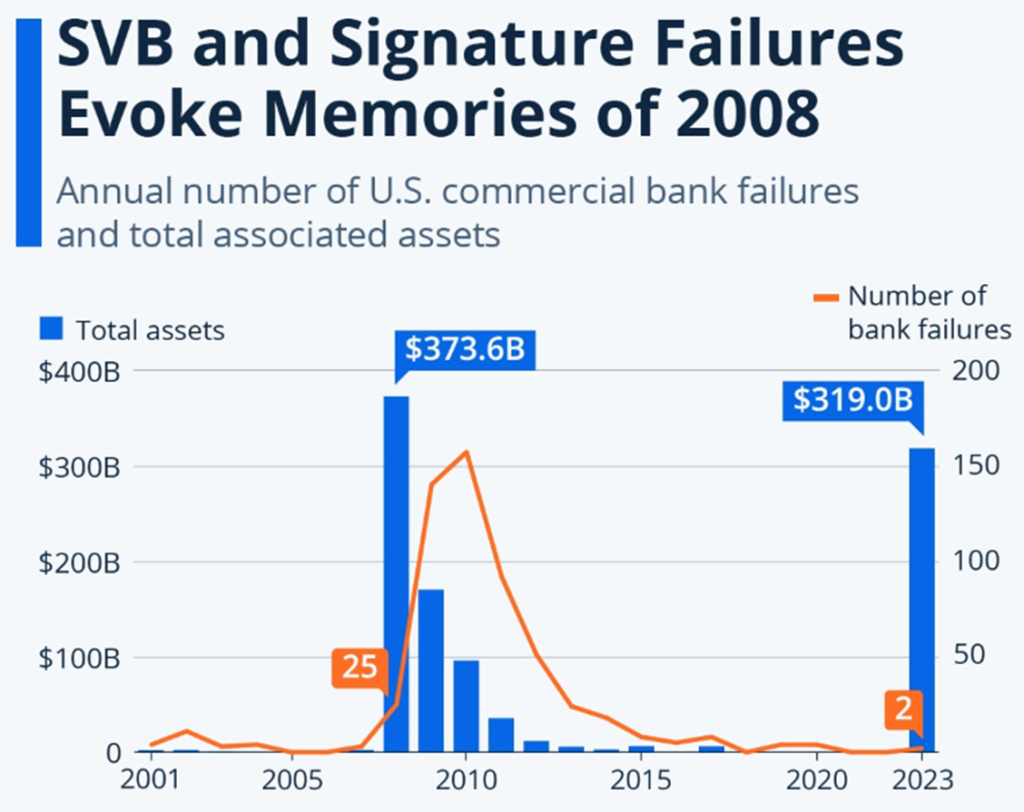

- Add bank failures to the mix of worries

- SVB’s failure is not a systemic issue so far

- Credit tightening helping Fed with inflation

- Big 4 banks act as safe ports in the storm

It is said that the 1920s was the first decade to have nickname. It became known as “the Roaring 20s” because of the sense of optimism and progress that prevailed after the darkness of WWI ended. For the US, it was the decade that cemented its leadership of the global economy as its economy grew by over 40 percent and incomes soared. In Canada, the Roaring 20s saw a surge in US investment into the country which allowed it to prosper from the boom of its much larger neighbor.

When the 1920s began, US Senator Warren Harding pledged a “return to normalcy” if voters would elect him as president. This messaging resonated with voters and played a big part in his ability to capture over 60 percent of the vote and become the 29th US president. Taking stock of the 2020s, a return to normal sounds appealing. It began with the pandemic and has transitioned to one of incredible challenges ranging from war in Europe, tensions with China and a surge of inflation.

Keeping with this theme of decades, in a previous newsletter we had referenced Vladimir Lenin’s quote that “There are decades where nothing happens; and there are weeks where decades happen.” So far, the 2020s has seen too many weeks where decades happen. Last month had one of those weeks when the US economy saw the failure of two banks (Silicon Valley Bank and Silvergate Bank) along with the liquidation of another (Signature Bank). Days later, the world saw the failure of Credit Suisse – a financial institution founded in 1856. A nearly 170-year-old institution sank in only a few short volatile days as Switzerland’s government quickly ushered it into the hands of competitor UBS. But it was the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) that caused the most angst.

What Happened to SVB?

Founded nearly 40 years ago, SVB was a California-based bank specializing in providing financing to venture capital backed firms. The venture capitalists who backed these firms were often well known and well-respected funders of startup firms. These startups would usually have a steep hill to climb in order to get financing from traditional banks due to the higher potential risk of their business. As its reputation and connections to the venture capitalists who supplied the initial funding to startups grew, its place in the venture capital industry was secured. In 2015, SVB said it served nearly two-thirds of all US startups and its own website had stated that at the end of 2022, 44 percent of

US venture capital backed technology and healthcare companies that went public did their banking with SVB.

In a strong capital raising environment, startups and other young companies can tap equity markets for capital by selling shares to the public. But rising interest rates and worries about the future of the economy made investors more cautious. This resulted in capital for these companies becoming scarcer.

As this segment of the economy began to slow, it also translated into a slowdown in borrowing by SVB’s customers. With its lending volume slowing down, SVB parked more of its deposits in longer term US Treasury bonds to earn incrementally higher interest rates. The problem was that SVB’s management did not account for the risk that these bonds would be worth substantially less than their purchase price as interest rates continued to rise. This made SVB vulnerable to failure.

SVB: Poor Risk Management

In its most basic form, banking is a simple business which takes in funds (deposits) from customers and loans these funds to customers who need to borrow capital. The bank makes a profit by paying its depositors a lower interest rate than it receives on the loans it makes to its customers. This lending fuels economic growth by facilitating both consumption and investment. Occasionally, economic conditions expose banks with poor lending and risk management of deposits.

Following the pandemic, central banks flooded the financial system with capital that caused bank reserves to swell across the global banking industry. As the reserves filtered through the financial system, bank deposits swelled. For SVB, its deposit base soared from $60 billion shortly before the pandemic to over $211 billion at the end of last year. Ordinarily, soaring deposits are a great thing for a bank but in the case of SVB, they mismanaged these deposits by investing too much of the deposits into US Treasury bonds that were vulnerable to large price declines.

US banking regulators allow banks to hold Treasury bonds since debt obligations of the US government are safe assets and should depositors show up in large numbers to make withdrawals – the US treasury bonds can be sold quickly in large amounts for cash so that depositor withdrawal demands can be met.

The problem for SVB – and for the broader US banking industry – is that as the US Federal Reserve began raising interest rates at the fastest pace in its history to combat soaring inflation, bond prices have fallen sharply. This has left US banks showing monumental losses on their bond holdings. Prior to the collapse of SVB, the US banking system had a collective loss of over $620 billion on its holdings of US government bonds.

The irony is that the bank failures raised worries about the economy and investors across the world rushed to buy US Treasury bonds. This raised the value of the bond holdings of the banking sector – albeit by nowhere near enough to erase the preceding losses. It is easy to be concerned about these losses at first glance but as the bonds edge towards maturity or should the economy continue to slow down, the bond losses will decrease.

It should also be noted that while the losses are immense they are nowhere near the value of the $23.6 trillion in assets held on the balance sheet of the US banking sector at the end of 2022. The health of a bank is measured by a multitude of factors but perhaps the most important factor is the level of regulatory capital or equity that the bank has on its balance sheet. The greater the level of capital on the balance sheet of the bank then the greater is its ability to absorb losses from its operations during an economic downturn. SVB’s ability to raise capital to shore up its balance sheet disappeared.

SVB: A Lightning Fast Demise

Prior to the collapse of SVB, the venture capital space was supported by a sense of optimism that up until recently seemed limitless. By the third quarter of 2022, investors had poured $151 billion into venture capital funds – which exceeded the prior full year record of $147 billion set in 2021. But the resolve of the Federal Reserve to tame inflation by the continued ratcheting up of interest rates has ushered in considerable caution throughout corporate America.

For the young companies in the process of pushing to establish themselves, economic uncertainty has made the access to capital somewhat more difficult as the providers of capital get more selective to account for the uncertainty. This has meant venture capital firms needed access to their deposits held at SVB and other banks more than in the recent past.

In early March, the credit rating firm Moody’s Investor Services informed SVB that it was preparing to downgrade its credit rating in response to the capital levels of the bank amidst the losses it was taking on its bond holdings and the trends in its underlying business. By March 8th, following Moody’s public announcement of its decision with respect to SVB and a tweet from an influential venture capital investor for depositors to get their money out of SVB, investors began a lightning fast run on the bank. On March 9th depositors withdrew $42 billion from their SVB bank accounts – almost 25% of the bank’s total deposits! By the next day – less than 48 hours later since its spiral began – SVB management informed US regulators that its customers were coming for another $100 billion of their deposits. At that point, the regulators shut the bank down and promised depositors their deposits would be guaranteed. It should be noted that 94 percent of SVB’s deposits were not covered by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) which protects depositors if a bank were to fail. This is because the FDIC covers only the first $250,000 of a depositor’s account balance and many of SVB’s customers had millions of dollars in some of their accounts.

Fears of a New Financial Crisis

It seems unimaginable that a bank that was unknown to so many until its collapse could send shockwaves around the world and policymakers scrambling to calm down panicked financial markets (See graphic above). Investors began to worry that a new financial crisis similar to 2008 had begun.

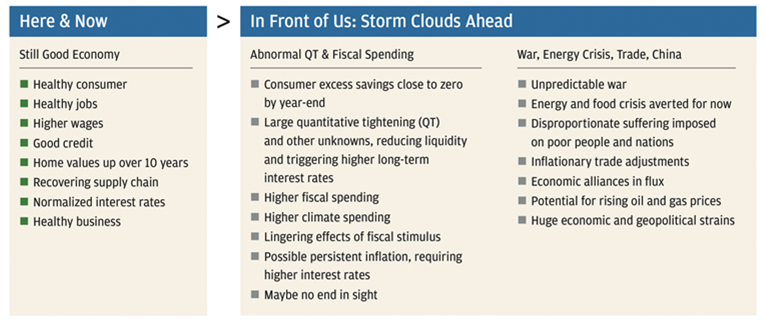

Perhaps the worst word in financial markets is “contagion” which is when fear spreads across markets and nations—causing a downward spiral that engulfs the global financial system. While it cannot be ruled out that other banks will not also suffer the fate of SVB, it seems thus far that the financial sector is coping with these stresses. What is unknown is what the impact will be upon the economy. As the figure shown below, the list of challenges is significant for the US economy but thus far the economy continues to be resilient.

Can SVB’s Failure Induce a Recession?

Prior to SVB, the recession debate was already raging. It is said that the Federal Reserve raises interest rates until something breaks. That something happened to be SVB which in turn broke Credit Suisse. Thus far, contagion has been contained as policymakers were quick to heed the lessons learned from the 2008 Great Financial Crisis and ensured that not a single SVB depositor would lose any of their deposits. This helped to quickly head off the potential of a systemic threat to the banking industry. Thus far, it seems that the global banking industry was tested and has proven resilient.

Prior to last month’s bank failures, bank lending was already beginning to retrench. But the last two weeks of March saw a record pace of contraction in lending by US banks. Recent data shows that commercial bank lending fell $105 billion in the last two weeks of March. Most of this decline was concentrated in real estate, industrial and commercial loans. Significantly, 75 percent of the decline in lending came from small commercial banks. As Jamie Dimon, CEO of US banking giant JP Morgan told shareholders in his annual letter “…while this crisis is nothing like 2008…It has provoked lots of jitters in the market and will clearly cause some tightening of financial conditions as banks and other lenders become more conservative.”

Will the Fed Declare Victory?

It is reasonable to expect that the retrenchment in global bank lending and the impact on business and consumer psychology of bank failures will restrain the economy in the months ahead. Some economists have predicted that the change in bank lending practices from the failures will have the same effect as a quarter percent increase in interest rates. Policymakers will welcome this because it makes their job of restraining inflationary pressures easier. Some economists believe that the fallout from these events will leave the US and other central banks more confident that the war on inflation has been successful enough to declare victory and that means easing up on interest rate increases.

From our perspective, it cannot be emphasized enough that the current banking challenges are nothing like those of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis. In fact, this crisis has shown that the largest US banks are seen by depositors and investors as safe ports in the storm.