Assessing the Yield Curve’s Economic Forecast

In This Issue

- What is the yield curve and why are markets focused on it?

- Financial stress conditions have eased and remain at multi-year lows

- Earnings estimates have been reduced and some analysts are looking for an earnings recession

One of the central topics at the forefront of the markets’ collective attention is the yield curve. In fact, it is likely that the yield curve has never been such a popular topic as it is today. So what is the yield curve and why is it talked about so much? The yield curve is a line graph of prevailing interest rates (yields) at different points in time. This curve is a reflection of where short-term interest rates sit relative to longer-term interest rates.

Normally, the yield curve slopes upward because short term bonds offer lower yields than longer-term bonds. This is because lenders, such as banks or investors who buy a longer-maturity bond, demand a premium interest rate to offset future risks, such as inflation or credit risk where the borrower might not be able to pay the loan (bond) back (i.e. default).

However, the yield curve is not static and continually changes its shape in such a way that it will reflect either economic optimism or fears of a recession as new economic data comes in. Over the last several months, markets have become preoccupied with the message being sent by the yield curve. Specifically, many are wondering if the yield curve is forecasting whether the economy is headed into a recession.

Currently, the yield curve in the US has flattened and is threatening to invert. An “inversion” occurs when short-term rates in the US move higher than longer-term interest rates. This has largely come about because the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) has been raising interest rates since December 2015 and trying to push up short-term interest rates to reflect US economic strength as evidenced by the lowest unemployment rate in about 50 years. However, the Fed’s ability to influence interest rates is anchored to the short end of the curve (i.e. short-term interest rates). The longer end of the yield curve is influenced by investors in the bond market and reflects their collective expectations of future Fed policy decisions, inflation expectations and optimism or pessimism about the economy.

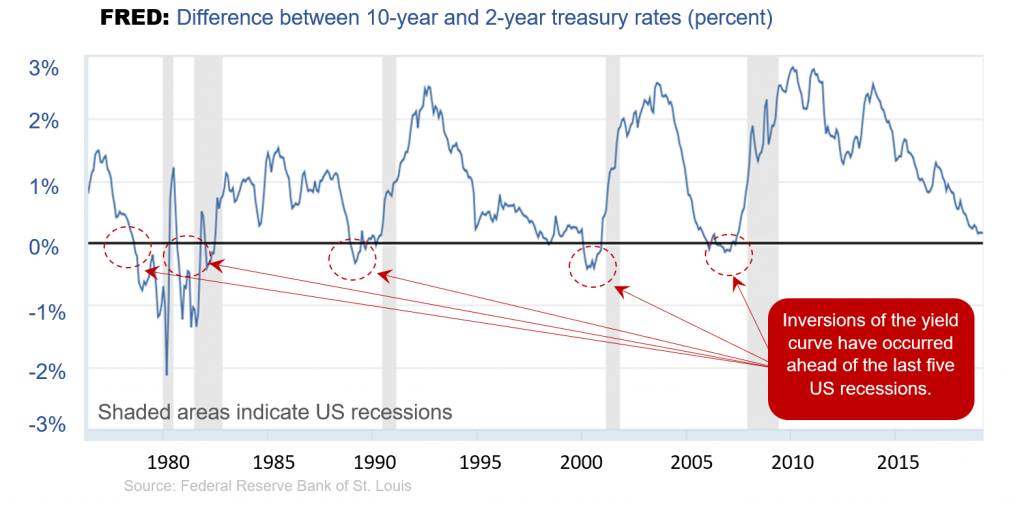

We are seeing a duel of sorts take place in the bond markets where the Fed has been pushing the short-term rates upwards and the bond market has begun pushing down the long-term rates downwards. The bond market and in turn the equity markets felt the Fed was likely overdoing it and its tightening would cause the economy to slow down. The result of this duel was that the spread between the short-term and long-term rates has narrowed, causing a flattening of the yield curve. This can be seen in the chart above. The shaded areas represent the start and end of every recession since 1980.

It is not only in the US that markets are pushing interest rates lower. The US and Canada are the only two major economies that have seen their central banks raise interest rates over the last several years. In Europe, the European Central Bank (ECB) has walked back its plans to begin raising interest rates and is content to sit on the sidelines for the time being. Globally, the amount of bonds yielding negative interest rates (bond holders are paying the borrower for the privilege of lending them money) has risen from $6 trillion in October 2018 to $10.5 trillion only six months later. This further underlines the concerns amongst investors that the global economy is slowing down.

Does History Repeat Itself?

Based on historical parallels, an inversion of the yield curve has preceded every recession over the last 50 years; this has fueled fears about an impending recession. However, it is important to note that following a yield curve inversion, a recession has taken anywhere from six months to 34 months to emerge. Therefore, even if the curve were to invert, it is difficult to be able to time the onset of the recession.

The Recession / Yield Curve Connection

The flattening of the yield curve is a signal from the bond market that it is worried about the economy and its ability to continue to grow. In addition, it is a signal that future inflation is nowhere to be seen. One outcome of an inverted yield curve is a weakening in bank lending as banks begin to earn less profits from making loans. In the most recent earnings announcements, the banks have already made this clear as they expect net interest margins to contract. This is because a bank’s role is to borrow funds at usually lower short-term rates and lend those funds at usually higher longer-term interest rates. The spread between these two rates represents the banks’ profits. However, with an inverted yield curve, the spread between the short-term and long-term rates narrows and the banks’ incentives to lend are greatly reduced. Not only is the profit margin eroded by the yield curve, but the banks could become worried about the possibility of an economic slowdown. As banks become less incentivized to extend credit (make loans) to their customers, it results in a vital lifeline of the economy being choked off.

Recession Is Not a Foregone Conclusion

As any economist will attest, trying to predict the direction of the economy with precision is a difficult exercise at the best of times. Throwing in complications, such as trade wars, tariffs, Brexit and geopolitical instability makes the scenario much more difficult. Even the Federal Reserve, which is thought to have some of the best economic forecasters and data collectors in the world, has been humbled trying to predict the economy’s trajectory. For example, in January 2008, a time when the last recession was already underway (known now with hindsight), Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke told the US House of Representatives that his forecast called for a slowing in the economy but no recession. Again, with hindsight, the recession was already underway, and the world’s most important economic policymaker had no idea.

While an inverted yield curve is not an economic positive by any stretch, it would be a mistake to extrapolate it into concluding a recession was imminent. Some economists believe that this time is different with respect to the yield curve. This is because there has been so much intervention by central banks around the world to try to keep interest rates pinned down that the signals are influenced by market-distorting policies and therefore are not as valid as they once were.

Backing Down

An old saying amongst investors—“Don’t fight the Fed!”—means that it has seldom been a good thing to invest in a way that does not align with the Federal Reserve’s monetary policies. In the second half of 2018, markets took notice of what was happening to the yield curve as it continued to flatten. Equity markets sold off sharply and investors saw this as the Fed being intransigent with respect to its stated goals of taking money out of the financial system through Quantitative Tightening (QT) policies. It is likely that it was the QT policies that had a greater impact on market volatility than the interest rate hikes.

As the chart below shows, the last two recession have been preceded by a rise in the financial stress index. The index was on the rise once again but the Fed’s abrupt policy reversal has calmed the stress index down—along with investor anxiety.

In response to the not-so-subtle signals being sent by the financial markets, the US Federal Reserve followed the European Central Bank’s example and backed down on following through with planned interest rate increases in 2019. As recently as December 2018, the Fed had signalled that 2019 would see at least two interest rates increases. Now, it has shifted to “zero” interest rates increases for this year. It has adopted a “patient” approach towards interest rates. No sooner had investors been cheered by this policy response that they began to collectively ask, “What does the Fed know that it would make an abrupt turn on its interest rate policy?”

It turns out the Federal Reserve has become concerned about the slowdown in China and Europe. But on a positive note, it is an unlikely probability that the US economy will go into recession because of an overseas slowdown. The US tends to export its problems to the world—not the other way around. However, any substantial slowdown abroad will be felt in the US.

Outlook For Equity Markets

Currently, earnings estimates are being reduced in response to slowing economic growth and some are calling for an earnings recession or a drop in corporate earnings. It is expected that first quarter 2019 earnings will see the first decline since 2016. At this point, there seems to be a disconnect between investor complacency and the potential for economic hurdles to be more persistent than might be expected.

According to FactSet, the financial data provider, there has been a rise in the number of companies reporting a reduction in earnings estimates. However, for companies in the S&P 500 index, so far 74% of the companies that have issued guidance on their profit outlooks have cut their outlook. The five-year average has been 70%. While this is in line with historical levels, the one difference is that companies that have cut earnings estimates have in fact cut their earnings estimates by 7.3%, whereas the five-year average is less than half of that at 3.2%.

A key factor that many will be watching for is continued progress on a US-China trade deal. With the two nations making up almost 40% of the world’s economy, any negatives or positives in their relationship will be felt globally. A rebound in China’s economic outlook will be a strong positive contributor to equity markets. The Chinese government has adopted several stimulus measures and have begun to balance the need for cleaning up its economic imbalances with the need for growing the economy. This will have a positive effect on Europe—and in particular Germany.

But perhaps more than trade frictions possibly easing, it is the easing of US interest rates that has had the biggest impact on financial markets returning to a calmer state. Now, investors are waiting to see if corporate profits will soon return to a steady state of growth or if economic growth will take some additional time to recover.