Push for More Stimulus Ignores Risks of Japan’s Experience

This September has been an eventful month for China. Apart from defending its assertion to vast areas of the South China Sea, it also hosted world leaders at the G20 Summit to discuss ways to raise global economic growth rates. All of the political leaders agreed that they needed to ensure that they had to fight the slowdown in global trade and get a commitment from each nation to adopt more fiscal stimulus measures (i.e. government spending).

Going into the summit, there was a widespread consensus that low interest rates are now increasingly ineffective tools for stimulating the global economy and have about run their course. Most central banks have made explicit admissions that there is not much that they can do to lift economic growth rates. In fact, it could be argued that the effect of such policies on capital misallocation and economic distortions is part of the problem – not the solution.

There is no doubt that there is a strong international consensus that more must be done by the international community. As Chinese President Xi Jinping stated to the other world leaders, “The world will be a better place only when everyone is better off.” However, the spirit of international cooperation breaks down due to each nation’s domestic political priorities and debt levels that limits the capacity for meaningful fiscal spending to help jumpstart their respective economies.

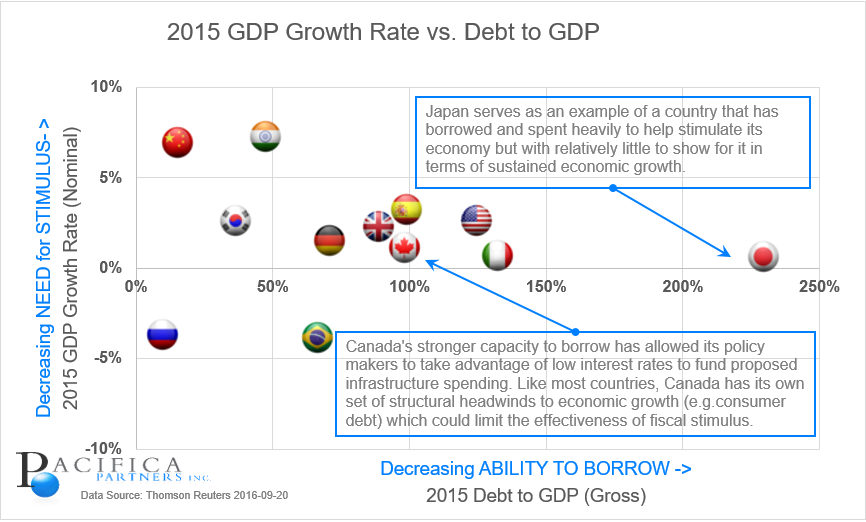

Leading up to and during the G20 Summit, Japan voiced its wish for more to be done on the fiscal front by the international community. For its part, no nation has gone to the extent that Japan has in order to kick start domestic economic growth. It has applied a monumental amount of fiscal and monetary stimulus but has had little to show for it over the last three years. As the chart above shows, Japan’s debt to GDP ratio dwarfs that of every other nation but still its economic growth rate has barely budged off of the 0% line.

In addition to Japan’s huge fiscal spending measures, its central bank has tried a massive currency devaluation designed to help its exports; negative interest rates to stimulate borrowing; bought back over 30% of all Japanese government bonds in order to help the nation finance its massive spending programs and has even tried to lift the Japanese stock market by purchasing tens of billions of dollars of Japanese stocks – making it one of the largest holders of equities in the country! This last item is especially concerning because assets (stocks) begin to trade not based upon what they are worth. Instead, investors build in an expectation that the Bank of Japan’s money will keep propping up the Japanese market. More importantly, the Bank of Japan has become a top 10 shareholder (owner) in 90% of the companies in the Nikkei 225 Stock Average.

Japan is not alone in this practice. Switzerland’s central bank has been trying anything it can think of to keep its currency from rising – to help stimulate its economy. It has accumulated nearly $130 billion in equities with the largest share being US equities – including Apple. Said another way, one of the largest owners of Apple is Switzerland’s central bank. This shows the desperate measures central banks have had to resort to in the absence of sustained help from governments on the fiscal spending front.

Government spending is a worthy endeavor as an economic fix – if it is spent on worthy projects that will create long term economic benefits. Japan spent most of the 1990s building “bridges to nowhere” that resulted in creating a short term economic blip with no long term benefits and a rising national debt load. In the last few years, it has gotten better at targeting its spending but sub-optimal decisions are still seen widely. One recent example includes government efforts aimed at building large tracts of homes in regions where the population is declining rapidly. This capital has gone largely wasted with no long term benefit to the economy and the homes largely sitting empty.

In Canada, the new federal government has taken to the fiscal stimulus route in a move largely applauded by economists. It has pledged an additional $60 billion in new infrastructure over ten years – aimed largely at public transportation and residential construction. This comes on top of the $60 billion pledged by the previous government. But Canada is in a unique positon of relative fiscal strength since its debt-to-GDP levels and ability to borrow at a low interest rate afford it the ability to embark on fiscal stimulus measures.

For Canada, this is expected to provide a modest boost to the economy. Canada’s unique challenge is that its consumers are amongst the most indebted in the world and its industrial sector has shrunk steadily since the last recession. Its reliance on commodity exports continues at a time that most commodity prices are weak. Fiscal measures to stimulate the Canadian economy are welcome but consumer spending and business investment must also do their part.

Short sighted “political projects” dressed up as fiscal spending measures will only pile on debt and create a “Japanification” of the G20. Over two decades of misspent stimulus measures have given Japan the largest debt load in the developed world while much of the structural economic challenges remain. As we come to the end of the road for low interest rate economic fixes, the structural challenges that have held down economic growth since 2008 need to be addressed. These challenges include falling global trade, stagnant labor productivity that holds down incomes; and lackluster consumer spending growth in most parts of the world. In addition, nations must think of ways to slow and reverse the demographic challenges of falling populations and ageing societies. All of these require cooperation amongst world leaders and long term thinking that does not always match what voters want to hear. Therein lies the challenge.