Trade Friction & Sliding Markets

Financial markets experienced some of the lowest volatility on record in 2017. The lack of gyrations in the market led some to call 2017 “boring” and others to complain that lack of volatility had reduced opportunities to buy good quality equities at attractive prices. However, 2018 is another story as last year’s tranquility has been replaced by a resurgence of volatility. Clearly, the death of volatility has been greatly exaggerated.

What is Driving Volatility?

One of the old sayings in equity markets is that “markets climb a wall of worry.” Essentially, this well-worn expression means that markets are especially efficient at pricing in the worries (uncertainties) about the economy or politics that grip the front pages of newspapers or other media outlets. The reason this saying has proven itself over time is that as long as market participants are worried about something, then financial markets will be left with room to grow (i.e. there will be attractive valuation opportunities in the markets). It is only when investors are ultra-confident that they tend to overpay for equities by throwing money at the markets (i.e. undervaluing risk) – leaving them vulnerable to disappointment and downside.

At the start of 2018, investors poured over $78 billion into US equity ETFs (exchange traded funds) in January alone — setting an all time record for inflows into the stock market. This was fueled in part by exuberance around the passage of the “Trump Tax Cuts.” As history shows, this type of overwhelming exuberance is seldom rewarded and seldom long lasting. Almost on cue, February saw a tidal wave of fear-fueled selling and volatility, which saw the market rise and fall in successive waves. This was enough to drop the US S&P 500 index by 12% from its highs before it rebounded to quickly recover almost 75% of this drop in a ten-day period. As past tendencies of investor behavior would predict, investors reacted by fleeing the very same markets that saw record buying the month before.

From our perspective, the sharp rebound in volatility has been driven by different factors. Initially, the downturn was fueled by investors (both individuals and institutional investors, such as hedge funds and others) who had bought equities and bonds with leverage (i.e. borrowing money to amplify returns) while betting that volatility would continue to remain anchored to their record-low levels of last year. Essentially, they bet markets would remain boring.

When interest rates rose more than expected across many parts of the world – led by the US – bonds and equities sold off. This caused a sharp drop in some of these investors’ portfolios and they were forced to pay back their borrowed money by selling their investment holdings. As they were forced to sell, this created even more pressure for others to sell. This repeated itself until the selling pressure exhausted itself.

Trade, Tariffs and Trump

At the start of the year, one of the propellants of optimism has been the synchronized global economic growth that had economists sounding the most upbeat since 2007. Last year, a record low was reached in terms of the number of countries in recession. In a short amount of time, optimism around the economy has been replaced by worries about international trade frictions leading to trade wars and a slowdown in economic growth.

During the 2016 Presidential election, then-candidate Donald Trump had made the strongest argument for a tougher US trade stance against other nations than any other presidential nominee in a very long time. Specifically, he cited the NAFTA agreement with Mexico and Canada as well as trade with China as being his chief concerns.

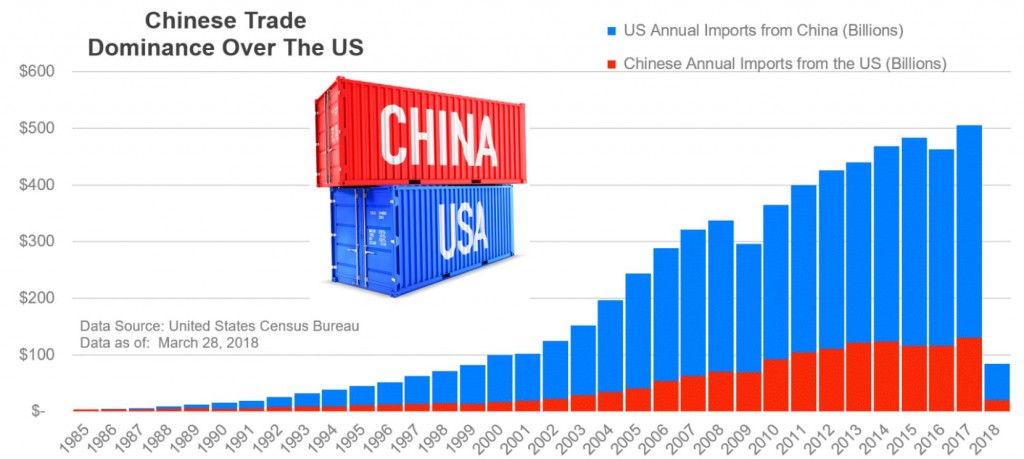

NAFTA negotiations are playing second fiddle to worries about a trade war with China. This is because there is a fear of the morphing of a selective tit-for-tat on tariffs between the US and China that could hurt economic growth and hinder the ability of US companies from selling their goods and services into the enormous Chinese market. As seen in Figure 1 below, US annual imports from China have exponentially grown since 1985.

Figure 1: Chinese Trade Dominance Over The US

Data Source: United States Census Bureau | Data as of March 28, 2018

The Trump Administration has stated that it wants to chip away at the trade deficit the US has with its trading partner nations. It says that these countries use unfair practices to hinder US exports through a breaking of international trade rules and what it terms as “stupid” trade deals. To solve the latter, the US has put the world on notice that it will no longer be business as usual. With respect to NAFTA, insiders who are privy to negotiations between the three nations have hinted that a new NAFTA deal is all but done.

It Is Down to China Then

That leaves China – upon which the US is looking to impose $50 billion of tariffs on Chinese exports to the US. It did not take China long to match this with $50 billion of tariffs on US exports to China. While things for a time had looked to be calming down, the White House announced that it was looking at an additional $100 billion of Chinese goods. It is important to note that these measures are not yet in effect – but they are proposed tariffs and will not go into effect for some weeks yet.

For those worried about the blowback on the economy should a full-blown trade war erupt, US exports to China represent about 0.7% of US GDP. Perhaps in recognition of this and China needing to exert maximum leverage, China has concentrated its proposed sanctions to impact the economy of states that were key to Donald Trump’s electoral win over Hillary Clinton.

The Trump Administration has received some support from across the political aisle on its get-tough approach with China. This is because for years China has forced many US companies who want to do business in China to hand over industrial and technology secrets. In turn, it has used this knowledge to build up its own companies by creating barriers to its domestic market for foreign companies and by providing enormous government subsidies to its domestic companies. China defends these practices by saying that it is still a developing country and therefore should get special privileges. This is not an argument that gets much support since China is the world’s second largest economy and has over $4 trillion in foreign exchange reserves.

Equally important is the fact that the US defense industry is facing severe challenges from years of China’s stealing of US defense technology. In a September 2015 speech, Former Defense Secretary Ash Carter stated that it is “evident that nations like Russia and China have been pursuing military modernization programs to close the technology gap with the United States. They’re developing platforms designed to thwart our traditional advantages of power projection and freedom of movement..” As Peter Singer, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation, made clear in a 2016 interview “… China has engaged in a massive intellectual property theft campaign. It’s hard to win an arms race when you’re paying the R&D costs for the other side.”

The iPhone Distortion

The trouble with all the trade talk is that there seems to be a lot of misinformation going back and forth. President Trump has stated that the US runs a $500 billion trade deficit with China. According to US government data, the trade deficit with China is less than $340 billion. Of this, it is likely that the trade deficit is even lower than $340 billion because of a shortcoming in how trade flows are calculated.

Using some simplifying assumptions, Apple’s iPhone can demonstrate how trade figures are not always what they seem. Apple assembles its iPhone in China but the programming and many of the components are made in the US. When the iPhone enters the US for sale to US consumers after its assembly in China, it might carry a value of $800/unit. This figure is recorded as an $800 export from China to the US – even though China only had a role in assembly of the iPhone. Not deducted against this $800 export is the value of Apple’s software and other components that were created in the US, which comprise the lion’s share of the iPhone’s value. All of those components on their own might carry little value – but put them together in an iPhone case and we have a very expensive consumer electronic device. It is estimated that Apple alone makes the US trade deficit look worse by about $30 billion. What effect would Intel, Microsoft or so many other corporations have on the trade deficit?

Focusing on the Wrong Kind of Deficit

Given the intellectual property issues outlined above with respect to China, it is understandable that the US is taking a harder line on trade. But most economists will probably agree that it is the budget deficit that should be getting Washington’s attention. If the same kind of zeal was applied to this issue, it would likely give the financial markets a bolt of confidence.

Markets are worried that at the very same time that the US Federal Reserve has begun to trim down its mountain of US government bonds, the rising US budget deficit (borrowing needs) will bring about an ever higher need to issue more bonds. As the increased supply of bonds from the Federal Reserve sales and increased issuance from the US Treasury hit the markets, these will force the price of the bonds lower and interest rates higher in order to mop up the supply.

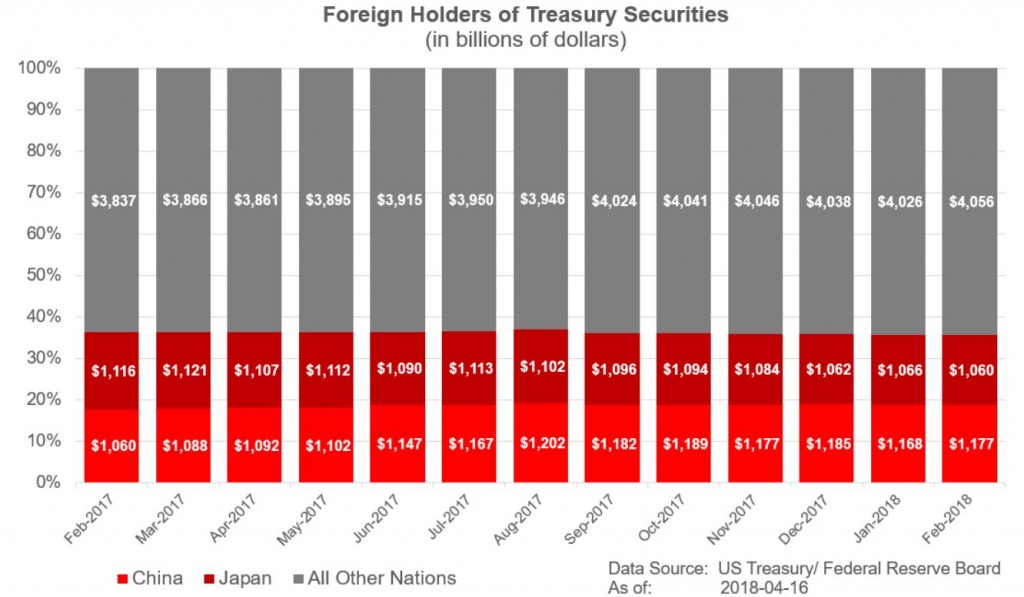

Some have wondered if the US is at the mercy of China and other foreign nations that hold so much of the national debt. As Figure 2 below shows, China and Japan hold over 30% of the foreign-held national debt obligations of the US government. For the US, it could be harder at some point to demand concessions when its largest creditors are the nations it is involved in a trade dispute with.

Figure 2: Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities

Data Source: US Treasury/Federal Reserve Board | As of April 16, 2018

Contrary to former Vice-President Dick Cheney’s opinion that “Reagan proved that deficits don’t matter,” the markets are concerned that the budget deficit is expected to continue to widen even though unemployment is at generational lows and the economy continues to move along at a steady though unspectacular pace. The worry revolves around the question of “What happens to the budget deficit when the next recession hits?” as government tax revenues tend to fall and spending requirements rise.

Trade Tensions and Market Volatility

Trade issues are causing concerns about economic growth and in turn are feeding into investor anxiety. Thrown on top of this are worries about higher US interest rates. Thus far, the Federal Reserve has continued to stress that it will continue its path of raising interest rates given how tight labor markets are. Workers – especially skilled workers – are in short supply but wages are still anchored. The Federal Reserve is being especially vigilant regarding rising wages.

In the coming weeks, we will see corporations report earnings and give their 2018 forecasts. This “guidance” will be important in setting the tone for the current year. If corporate earnings are in line with current expectations, then that should provide a supportive backdrop for equity markets.